'Balm for the healing of the nation': the wisdom of Latitudinarian civility

The message of Christian charity, delivered by Tillotson and his friends to the Englishmen who had experienced the national turmoil of the midseventeenth century, might have played not a small part in creating the comparative peace and stability of the next century.

This emphasis on the theological roots of civility, the ecclesiastical responsibility to promote civility, has surely some contemporary relevance in a cultural context in which religion is widely regarded as divisive, doing more harm than good. A 2017 global survey suggested that 49% of people agree that religion does more harm than good. In the United Kingdom, the figure is 62%. As the report accompanying the survey stated, "Countries which are most likely to believe that religion does more harm than good tend to be in Western Europe".

Almost certainly this is reflective of the post-9/11 world. It probably also has been influenced by the most effective aspect of the New Atheist creed, the historical critique of the wrongs of religion in general and Christianity in particular. Ironically, however, it also coincides with heightened partisanship and political division in the very societies most likely to say that religion does more harm than good. The cultural rejection of religion is occurring as we, at the same time, are also beginning to discern a profound cultural weakness - the absence of an account of the virtues and the common good which can sustain the norms of democratic pluralism.

In such a context, perhaps we should heed the wisdom of Latitudinarian civility, of the theological grounding it gives for moderation and sobriety in ecclesial life, and its critique of religious factionalism and Enthusiasm.

In order to demonstrate the Latitudinarian vision of civility, some extracts from the works of Tillotson can be considered. In the first (quoted in Birch's Life), Tillotson pays tribute to a deceased clerical colleague for his commitment to moderation, a virtue which he sees as inherent to the life and vocation of Anglicanism:

And I purposely mention his moderation, and likewise adventure to commend him for it, notwithstanding that this virtue, so much esteemed and magnified by wise men in all ages, hath of late been declaimed against with so much zeal and fierceness, and yet with that good grace and confidence, as if it were not only no virtue, but even the sum and abridgment of all vices: I say, notwithstanding all this, I am still of the old opinion, that moderation is a virtue, and one of the peculiar ornaments and advantages of the excellent constitutions of our church, and must at last be the temper of her members, especially the clergy.

In regretting that moderation "hath of late been declaimed against", Tillotson strikes a particularly contemporary ring. His Funeral sermon for Cambridge Platonist Benjamin Whichcote, Tillotson similarly lamented the rise of faction, partisanship, and divisiveness, "those wounds which we madly give ourselves". By contrast, Whichcote exemplified the virtues which could "balm for the healing of the Nation":

In a word, he had all those virtues, and in a high degree, which an excellent temper, great consideration, long care and watchfulness over himself, together with the assistance of God's grace (which he continually implored, and mightily relied upon) are apt to produce. Particularly he excelled in the virtues of Conversation, humanity, and gentleness, and humility, a prudent and peaceable reconciling temper. And God knows we could very ill at this time have spared such a Man; and have lost from among us as it were so much balm for the healing of the Nation, which is now so miserably rent and torn by those wounds which we madly give ourselves. But since God hath thought good to deprive us of him, let his virtues live in our memory, and his example in our lives.

Reflecting the classical orthodox affirmation that 'grace does not destroy nature', Tillotson in Sermon IV points to the temporal goods of religion:

Religion conduceth both to our present and future happiness, and when the gospel chargeth us with piety towards God, and justice and charity towards men, and temperance and chastity in reference to ourselves, the true interpretation of these laws is this, God requires of men, in order to their eternal happiness, that they should do those things which tend to their temporal welfare.

Sermon XXXIV has a significant warning against "Faction in Religion" as destructive of the virtues in the life of the Church, the individual, and society:

But besides these dangers which are more visible and apparent, there is another which is less discernible because it hath the face of Piety; and that is Faction in Religion: By which I mean an unpeaceable and uncharitable zeal about things wherein Religion either doth not at all, or but very little consist. For besides that this temper is utterly inconsistent with several of the most eminent Christian Graces and Virtues, as humility, love, peace, meekness, and forbearance towards those that differ from us; it hath likewise two very great mischiefs commonly attending upon it, and both of them pernicious to Religion and the Souls of Men.

First, That it takes such men off from minding the more necessary and essential parts of Religion ... Secondly, Another great mischief which attends this temper is, that men are very apt to interpret this zeal of theirs against others to be great Piety in themselves ... Therefore, as thou valuest thy Soul, take heed of engaging in any Faction in Religion ... Besides that, a man deeply engag'd in heats and controversies of this nature, shall very hardly eſcape being possess’d with that Spirit of uncharitableness and contention, of peevishness and fierceness, which reigns in all Factions, but more especially in those of Religion.

In Sermon XI, Tillotson identifies Anglicanism as particularly committed the sobriety which underpins civility. This also finds expression in "a due and just subordination to the civil Authority", to the polity as a means of securing civility and peaceable life:

I have been, according to my opportunities, not a negligent observer of the genius and humour of the several Sects and Professions in Religion; and upon the whole matter, I do in my Conscience believe the Church of England to be the best constituted Church this day in the world; and that as to the main, the Doctrine, and Government, and Worship of it, are excellently framed to make men soberly Religious: Securing men on the one hand, from the wild freaks of Enthusiasm; and on the other, from the gross follies of Superstition. And our Church hath this peculiar advantage above several Professions that we know in the world, that it acknowledgeth a due and just subordination to the civil Authority, and hath always been untainted in its Loyalty.

Perhaps some of the most important words I have read from a contemporary theologian regarding the Church's mission have been spoken by Andrew Davison:

isn’t it an absolutely central part of Christian mission today to present and embody accounts of what it means to be human that are attractive, sane and wise?

Tillotson's account of moderation as a virtue which underpins civility is suggestive of how the Church can articulate a vision of common life in polity and society that is "attractive, sane and wise". What is more, at a time when there is a search for philosophical, moral and spiritual foundations for the peaceable ordering of our common life, for liberal democracy and pluralism, it points to how Christianity can shape such peaceable, rational, and sober foundations for civility.

He came not to kill and destroy, but for the healing of the nations; for the salvation and redemption of mankind, not only from the wrath to come, but from a great part of the evils and miseries of this life. He came to discountenance all fierceness, and rage, and cruelty, in men one towards another; to restrain and subdue that furious and unpeaceable spirit, which is so troubleſome to the world, and the cause, of so many mischiefs and disorders in it; and to introduce a religion which consults not only the eternal salvation of men's souls, but their temporal peace and security, their comfort and happiness in this world (Sermon IXX).

------------

Birch's 'Life' of Tillotson and Sermon IV are found in Volume One of the 1820 collection of The Works.

The sermon at Whichcote's funeral, Sermon XXIV, Sermon XI, Sermon XIX (preached before the House of Commons in 1678) is in Volume Two.

Sermon XXXIV is in Volume Three.

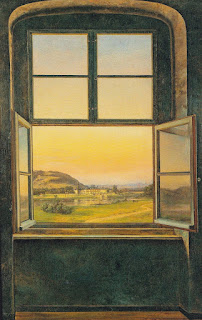

The painting is Johan Christian Dahl, 'View of Pillnitz Castle', 1823.

Comments

Post a Comment