'Through the grave and gate of death': commending an Old High Easter Eve

To be clear, this essay is not for those who observe the Vigil and who do it well. It is for those of us who do not observe it, assuring us that the liturgical and theological coherence of a traditional Prayer Book Easter Eve has much to commend it.

Below, the section of the essay which considers Ante-Communion on Easter Even.

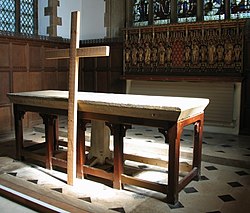

Alongside Mattins and Evensong, there is also the Ante-Communion of Easter Eve. Ante-Communion on this day has a particular resonance, gathering the Church before the Tomb, “the grave, and gate of death,” in the knowledge of the Resurrection. It orients us towards and assists in preparing us for the celebration of the holy Sacrament on Easter Day. The Epistle and Gospel at Ante-Communion establish the doctrinal focus of the day: in the words of Wheatly, “the Gospel treating of Christ’s body lying in the grave,the Epistle of his soul’s descent into hell.” The Ante-Communion, then, is the high liturgy of Easter Eve, prayed at the Holy Table, with the reading of the Commandments and the profession of the Nicene Creed marking the solemnity of the day.

The readings at Mattins and Evensong can be understood as commentary on the Epistle and Gospel at Ante-Communion. The Gospel reading – Saint Matthew’s account of the burial – provides a different aspect to the Lucan account at Mattins, ending with the sealing of the Tomb and the setting of a watch. This emphasizes the reality of the creedal profession “and was buried,” while also pointing us to – in the words of Saint Paul – “the power of his resurrection.” Indeed, the Creed recited immediately after the reading of the Gospel is an expression of the abiding joy with which the Church reads the account of the Lord’s burial: “And the third day he rose again according to the Scriptures.”

It is the epistle of the day, of course, which – as Wheatly notes – particularly proclaims the harrowing of hell: “he also went and preached unto the souls in prison.” As with the Gospel, this too is a declaration of the Resurrection, indicated by the Epistle referring to “the resurrection of Jesus Christ.” This is also related in the Epistle to our Baptism – which “doth … now save us” – setting the context both for the praying of the collect with its Baptismal reference, and the further exposition of the day’s relationship to Baptism in the second lesson at Evensong.

In a particular manner, then, the Ante-Communion of Easter Even, supplemented by Mattins and Evensong, with Cosin’s collect prayed at each of these liturgies, ensures that the Church’s observance of this day does not become a role-play in which we make-believe that the Resurrection has not ‘yet’ occurred. No, through the reading of Scripture in the Church’s liturgy throughout the day, we perceive that commemoration of the Lord’s burial and descent into hell – no less, indeed, than the commemoration of the Cross itself on Good Friday – is entirely dependent upon the truth of the Resurrection. It is only in light of the Resurrection that these events are salvific.

1662 thus provides a rich and full liturgy for Easter Eve, in which the themes of the Lord’s burial, descent into hell, and our Baptism are complemented by the call to fasting and abstinence ahead of the great feast. Add to this the absolution pronounced at Mattins and Evensong, ensuring that we approach the Holy Table on Easter Day ‘shriven,’ and we can see how an Old High Easter Eve does not require the mid-20th century attempt to reinstate an Easter Vigil.

Comments

Post a Comment