Charles Inglis Day: a day to praise the old Toryism of country rectors

The chief defect of the Churchmanship of Nova Scotia, is a lack of intellectual breadth, the result of the isolation of the diocese from great centres of thought and action, and there have consequently been many places where the attitude of the Church towards other religious bodies has been narrow and intolerant ... In Nova Scotia the Church may hold her own, but she can never gain greatly until her clergy come to understand that she is not simply the ancient Church of England, or the Church of the Tory people of the American Revolution, but that she is also a Church with infinite powers of adaptation to the intellects and hearts of nineteenth century men and women.

Could a more definitive criticism have been uttered by a late 19th century graduate of Harvard than "lack of intellectual breadth" and "isolation ... from great centres of thought"? Harvard, of course, naturally being the greatest of such great centres.

The Tory Anglicanism of Nova Scotia, Eaton declared, needed to become more like the Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States in which he served; more like the Harvard from which he graduated; more like the enlightened New England Protestant culture which continued (for the time being) to dominate the life of the Great Republic:

In the United States, any pre-eminence the Episcopal Church may have attained, has been the result of an intelligent recognition by her members, of the great issues of thought on which religious men have become divided, the broader intellectual movements back of present denominational differences. In Nova Scotia, the clergymen of the Church have too often made prescriptive authority and tradition do duty for clear thought and fair-minded appreciation of the positions of other Christian men. For this the complete cure can be found only in a broader university training, in which men of widely different opinions, and yet bound to respect each other's intellectual powers, shall come together in the freest social intercourse. It is, in great part, to this unrestrained mingling of able young men of all denominations in the various colleges and other institutions of learning, that the Churchmanship of the United States owes its well-recognized comprehensiveness and breadth.

Eaton here provides a Whig account of Anglicanism: cosmopolitan, enlightened, progressive. This Whig account, as Eaton makes clear, contrasts with the Toryism of the Church of Charles Inglis, first bishop of Nova Scotia, and commemorated in the Church of Ireland calendar on this day. Eaton is not alone in his Whiggish criticism of the provincial Toryism of the Church of Inglis. Historian Judith Fingard - echoing Eaton - described the Church of Inglis as "conservative and unimaginative": are there more offensive terms that could be uttered by a respectable Whig sensibility?

What, however, if it was the provincial Toryism of Inglis which enabled Anglicanism to take root in the soil of the Maritimes in a manner more resilient and more enduring than did Whiggish Episcopalianism in the "great centres of learning" celebrated by Eaton? What if the Toryism of Inglis contributed to a more vital Anglican culture in the Maritimes than is now found in those "great centres of learning" lauded by Eaton but in which Episcopalian presence is now almost irrelevant? What if King's College Chapel, the Atlantic Theological Conference, and rural parish churches throughout the Maritimes are the fruit of the Tory vision of Charles Inglis?

The richness, for example, of the Anglican witness of King's College Chapel is the fruit of Inglis' intention to establish a robustly Anglican college. We might blush, of course, at the determination Inglis showed to create an Anglican establishment, but it was that determination which rooted a robust, resilient, and rich Anglicanism. For Eaton, however, the foundational Anglican identity of King's College was "obnoxious ... unjust and foolish" and characterised by "religious narrowness": it should, in other words, have been more like Harvard.

One can also easily imagine how Eaton would have sniffed at the Atlantic Theological Conference, shaped by the deep Anglicanism of Robert Crouse (described by Ron Dart as a 'prophetic Tory'), drinking from the wells of Prayer Book and Articles. One can almost hear Eaton disapprovingly refer to such "prescriptive authority and tradition", while yet being more than a tad surprised by the very different theology now pursued in his "great centres of learning".

As for the native High Church tradition of the Maritimes (of which the Atlantic Theological Conference is a contemporary expression), it flows from an Anglican way nurtured and maintained by Inglis, standing in sharp contrast to Eaton's celebration of the "well-recognized comprehensiveness and breadth" of Episcopalianism in the United States. As Inglis instructed the clergy of Nova Scotia in his 1788 Primary Visitation Charge:

As Clergymen of the Church of England, You are under solemn engagements to conform to the Liturgy, Offices and Rubrics contained in the Book of Common Prayer.

Institutions rooted in place and history. Tradition as wisdom, received with gratitude. Inherited allegiance shaping a common life. Such was the Tory vision - what Dart calls the "Canadian High Tory way" - of Charles Inglis, an alternative to Eaton's cosmopolitan, enlightened, progressive Whiggery. Or, as Samuel Johnson defined 'Tory', "One who adheres to the ancient constitution of the state, and the apostolical hierarchy of the church of England, opposed to a Whig".

"No man was so surely a Tory as a country rector", observed Trollope in Barchester Towers. And this is what contemporary Anglicanism needs: more of the old Tory virtues of Inglis and previous generations of country rectors. The Whiggish Anglicanism of Eaton, after all, has been relegated to cultural irrelevance in those "great centres of learning" which he regarded as safely ensuring the cultural presence of Episcopalianism, incapable of withstanding the cold cultural winds of secularism. The old Tory virtues, however, could aid in sustaining the Anglican way in the face of those cold winds.

To be clear, this is certainly not at all to recommend the politics of reaction (itself profoundly unconservative). Nor is it to urge support for political parties which masquerade as Tory but whose first allegiance is pledged to the free market and low taxes, rather than peace, order, and good government. It is, however, to suggest that the old Tory virtues of Charles Inglis, and of Trollope's country rectors, are needed by contemporary Anglicanism in North Atlantic societies. It is to suggest that the means of sustaining Anglican life and witness in a secular age are particularly valued by the old Toryism of Inglis: institutions (in church and state, for Inglis knew well the importance of political institutions to enable a community to know "rest and quietness") rooted in place and history, not the least of which is the parish; the theological riches of Anglicanism's historic Reformed Catholic tradition; an allegiance to the Book of Common Prayer, with Mattins and Evensong, the Sacraments, and the occasional offices, sanctifying the ordinary round and the common task.This, then, is a Charles Inglis Day proposal for contemporary Anglicanism in North Atlantic societies: much less Eaton, much more Inglis; much less fashionable Whiggery, much more of the old Tory virtues.

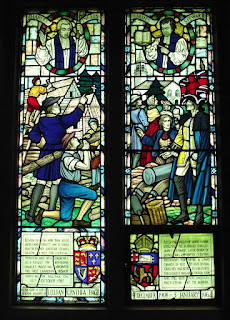

(The first picture is of a stained glass window in the Church of the Ascension, Hamilton, Ontario - one of a series of windows celebrating Canadian Anglican pioneers - showing Loyalists settling in Canada after the Revolutionary War, with bishops Charles Inglis and James Stewart look on. The second is of Trinity Church, Kingston, the oldest Anglican church in New Brunswick, built in 1789 by newly-settled United Empire Loyalists from Connecticut and New York.)

Comments

Post a Comment