Enthusiasm, Bishop Butler, and Old Hat history at Lambeth

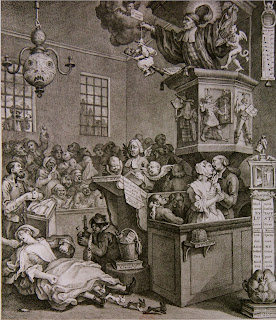

His views on the 18th century church, however, are not without significance and not least because caricaturing 18th century Anglicanism has frequently been a sign that those involved are seeking to reorder Anglicanism. Ryle, for example, promoting his own brand of Victorian low church evangelicalism, absurdly regarded 18th century Anglicanism as defined by "natural theology, without a single distinctive doctrine of Christianity, cold morality, or barren orthodoxy". Newman famously condemned "the last miserable century", which actually works rather better as a description of the 19th century and the consequences of Tract XC. Nicky Gumbel, of Alpha fame, entirely ignoring the vibrant culture of lay piety in Georgian Anglicanism, has evoked the myth of a tired, out-of-touch established Church presiding over a period of "very low religious practice".

Historical research of recent decades has robustly refuted these caricatures of 18th century Anglicanism (the Whig historiography described by historian J.C.D. Clark as 'Old Hat' history), so much so that contemporary Anglican accounts of the 18th century are now deeply embarrassing, indicating the extent to which many clergy and commentators clearly have had no meaningful engagement with serious ecclesiastical history.

One might have expected, however, that an Archbishop of Canterbury, speaking in front of an international gathering of Anglican bishops, with the secular media paying attention, would have taken care not to repeat a view of Anglican history which serious scholarship has debunked.

But no.

The Archbishop's second keynote address included a well-known trope regarding 18th century Anglicanism:

The East India Company which ruled most of India until 1856 and controlled the bits it didn’t directly rule banned the singing of the Magnificat at Evensong, for fear that the indigenous people of India might get the feeling that that God might be on their side, against tyranny.

A well-known, very comfortable trope. Comfortable because it ensures that the Magnificat safely critiques others: 18th century imperialists, big business, nasty right-wingers not prepared to confess the sins of imperialism. As opposed to, say, those who are part of a progressive consensus that does not upset readers of the Guardian and their privileges vis-a-vis the deplorables. (It is a simple rule of reading Scripture: if I think that the challenging words of Jesus, the prophets, and the Magnificat are primarily referring to others - with whom, conveniently, I happen to disagree - rather than to me, I am not reading Scripture rightly.)

A well-known, very comfortable trope ... for which there is no historical evidence. There are plenty of sources which repeat 'the story' but do not provide evidence from primary sources. A Church Times review of a history of the East India Company and religion began by repeating 'the story' before going on to say, "whether or not that is true". When 'the story' is told, it is often associated with Anglican missionary Henry Martyn. There is, however, no reference to this in John Sargent's 1819 A Memoir of the Rev. Henry Martyn. There also does not appear to be any reference in the two volume Journals and Letters of the Rev. Henry Martyn.

When I recently raised the issue on Twitter, a historian of religion and British imperialism stated there was no archival evidence to confirm 'the story' in general or Martyn's use of it in particular.

Also worth noting is that the Archbishop's description of the relationship between the East India Company and "the indigenous people of India" is incredibly simplistic (as indicated by Jeremy Black's review of a recent history of the Company). A Christian critique of power really should indicate rather more thought than a first year undergraduate speaking to one of the very many revolutionary socialist groupings in a university.

It does, however, indicate a willingness to repeat caricatures of 18th century Anglicanism and invoke them in contemporary Anglican debates, a willingness all too evident in the second reference to the 18th century in the Archbishop's address:

God’s church preached violent crusades, organised the inquisition, burned people at the stake. God’s church covered up the sins of imperialism, took vast sums of money from slave traders. God’s church rejected renewal where it did not fit established patterns.

When Wesley came in England in the 18th century and literally tens of thousands of people in the poorest areas of the country came to faith in Christ a bishop at the time - I think it was Bishop Butler, an ancestor of mine ... said to him ‘your enthusiasm is a very wicked thing Mr Wesley, a very wicked thing indeed’.

God’s church sought to eliminate the First Nations and indigenous peoples from colonised territories, those peoples whose cross I’m wearing today, as is Caroline.

God’s church fanned the flames of antisemitism and provided a seedbed and a theology for the persecution of the Jews and ultimately for the Holocaust.

It would have been helpful if the Archbishop had actually used Bishop Butler's recorded statement: "Sir, the pretending to extraordinary revelations and gifts of the Holy Ghost is a horrid thing, a very horrid thing". Now, while this was indeed the 18th century definition of 'Enthusiasm', I am somewhat sceptical that all the gathered bishops of the Anglican Communion, journalists, and commentators will have been aware of this.

That aside, we might also guess that John Wesley himself would be astounded at the suggestion that Butler's comment should be placed alongside the Crusades, the Inquisition, the treatment of the First Nations, and (in a particularly shameful comparison) the Holocaust.

That Christianity and the churches should examine and repent of those attitudes and actions which promoted violence, oppression, and genocide is, I hope, a given. Placing Bishop Butler's theological critique of John Wesley in that process is, quite frankly, dangerous nonsense which radically undermines the serious work of penitence for past corporate sins.

In addition to this, Butler - a champion of Christian orthodoxy against Deism - was right. Claiming "extraordinary revelations and gifts" which demeaned the Sacraments of Baptism and Holy Communion, the ordinary prayer and worship of the parish church, and the practical, quiet piety of the Georgian Anglican laity was, and is, a theological error to be challenged and refuted. As Richard Mant (later a bishop in the Church of Ireland) stated in his 1812 Bampton Lectures against "our modern Enthusiasts in their narrations of ... violent and extraordinary inspirations", an emphasis on the need for "extraordinary revelations and gifts" undermined the ordinary working of grace through the Sacraments:

And if a man can bring his mind to think thus meanly of baptism, ordained as it was by Christ himself, with a promise of salvation annexed to its legitimate administration; what will he think of Christ's other ordinances? What of the other sacrament, the holy communion of Christ's body and blood? If the spiritual part of baptism be denied, why should the spiritual part of the communion be allowed? If water be not really the laver of regeneration, why should bread and wine be spiritually the body and blood of Christ, and convey strength and refreshment to the soul? Surely it is not too much to affirm, that the stripping of one of God's ordinances of that, which constitutes its essential value, has a natural tendency to bring the efficacy of the others into question, and to diminish at least, if not to annihilate, a man's respect for them as means of spiritual grace. In this condition perhaps he will continue, sometimes exulting in hope, and sometimes sunk in despondency; waiting for an extraordinary impulse of the Holy Spirit, and neglecting the means of procuring his ordinary sanctifying graces.

The failure to recognise in any way the theological significance of Butler's critique of Wesley is not a matter without contemporary relevance. It overlooks, for example, the resurgence in 'Enthusiasm' in Christian, Islamic, and secular forms. A Christian critique of such 'Enthusiasm' is a necessary part of responding to the Apostolic exhortation to live "soberly", knowing that this contributes to a good and just communal peace.

What is more, caricaturing Butler's critique undermines the 'ordinary' Anglicanism of the parish church, in which the cycles of prayer and sacrament, the sanctification of domestic and civic duties, and a quiet, sober piety are characteristics which shape the Christian life. Caricatures of 18th century Anglicanism often represent a 'weaponising' of church history in order to dismiss this ordinary, sober Anglican experience as a meaningful way of living out the Faith.

It does not get headlines. It does not produce outraged statements. Nor does it engage the activist base of ecclesial Left or Right. An Archbishop of Canterbury repeating Old Hat caricatures of Georgian Anglicanism, however, may have just as much - perhaps more - significance than other high profile debates for the average parishioner in ordinary English, Irish, Welsh, or North American parish churches. And we might note that both ecclesial Left and Right routinely engage in using stereotypes of 18th century Anglicanism as a means of promoting their 'prophetic' stances. Reverently sharing in Mattins; hearing a sound, thoughtful, unflashy sermon; praying to be "godly and quietly governed", for rain (particularly this year), for the bereaved family in the parish; seeking in sober fashion to live out in daily life the call to be "in love and charity with your neighbours": when a historical narrative which favours supposedly prophetic "extraordinary revelations and gifts" is favoured over the "godly and decent order", it is not without profound significance for the future of Anglicanism.

I'm thoroughly enjoying a leisurely read through this blog, as and when time permits. Please keep it coming. I'm keen to learn more, but also to see the application to today's situation. There is a depth & nuance here that I don't see in many other places. God bless.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your very generous and encouraging comments.

Delete