Life, culture, meaning: Anglican humanism in a secular age

From the article by Frances Ward in the Church Times, on the late Roger Scruton:

His secular friends insist that Scruton continued to be an atheist; that his Christianity was merely cultural Anglicanism. It was that, certainly - but also more. He regained his religion through philosophy, not as a leap of faith, but as an appreciation of a deep ordering to life, culture, and meaning which ultimately leads to God.

Not only is this an excellent description of Scruton's Anglican faith, it also summarises how Anglicanism has traditionally engaged with culture and society. A rich natural theology has underpinned such Anglicanism. Yes, it has been rightly and necessarily qualified by a robust Augustinian recognition of original sin, but this has not been interpreted so as to obscure the meaning of the first article of the Creed, that God is the maker of heaven and earth. In other words, the "deep ordering to life, culture, and meaning which ultimately leads to God" can yet be discerned, is sanctified and celebrated in the Church's life, and is a participation in the life of the Triune God.

Two recent accounts of Anglicanism, given by influential theologians, emphasise how this understanding can continue to shape Anglican life and witness. John Hughes in his 2013 essay 'Anglicanism as Integral Humanism: A de Lubacian Reading of the Church of England' stressed how the traditional Anglican relationship with culture and society - given expression in a range of "very concrete material [pastoral, sacramental, civic] practices" - should be understood not according to "the customary Erastian and latitudinarian lines" but, rather, as a vision of society and culture "flowing from and to him, who is the Alpha and Omega of all things".

Alongside this is the description given by John Milbank of Anglicanism's "hidden coherence":

refusing ... any facile separations between the sacred and the secular or between faith and reason, grace and nature ... sturdily incarnated in land, parish and work, yet sublimely aspiring in its verbal, musical and visual performances.

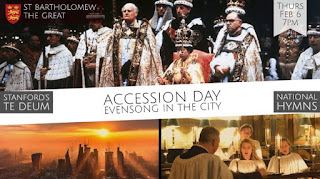

In both accounts we see how the Anglican way sets before us and draws into the "deep ordering to life, culture and meaning which ultimately leads to God": in the occasional offices sanctifying defining moments at the beginning, in the midst, and at the end of our earthly lives; in the quiet and native beauty of Choral Evensong; in state prayers understanding civic life as proceeding from and oriented to God's life, goodness, and communion; in place, community, and history caught up in the life of the parish church.

The late 20th and early 21st centuries have been marked by a rather catastrophic loss of Anglican in both this vision of the Church's relationship with culture and society, and in the "very concrete material practices" which have embodied it. (Sam Brewitt-Taylor's superb study explains the theological and ideological background this.) In their place, a range of sectarian proposals have been embraced: from Alpha to 'Jesus Movement', all underpinned by post-Christendom theologies which, in the words of Hughes, have abandoned "the possibility of a Christian culture" in "a strange mixture of two theological streams: evangelical Protestantism and liberalism". Such anti-Christendom theologies become self-fulfilling prophecies, undermining and rejecting the very practices which manifest culture and society as called to fulness in Christ, uninterested in these practices manifesting the "deep ordering to life, culture, and meaning which ultimately leads to God".

How might the classically Anglican vision and ethos then be retrieved? Perhaps three suggestions may assist such the beginning of such a conversation.

Firstly, there needs to be a renewal of the historic Anglican vision of natural theology. As Ward notes, Scruton himself significantly contributed to this with his The Face of God (2012) and The Soul of the World (2014), "question[ing] what humanity loses when God is effaced from the human condition". A more confident assertion of the naturalness and goodness of religious belief and the Christian revelation - once commonplace Anglican teaching - is required.

Secondly, a renewed confidence is required in the occasional offices, freed from the constraints placed upon them by liturgical revision, not the least of which constraints is the notion that adult baptism, rather than infant baptism, is the norm. The desire for meaning still marks birth, marriages, and death in a secular age, with humanist celebrants increasingly evident. The idea that the Church should - in a recognition that 'Christendom has gone' - retreat from such defining moments, and not use it occasional offices to unveil a meaning greater and infinitely more humanist than that offered by banal secular alternatives is only to reinforce the assumptions of secularism.

Thirdly, retrieving the civic vocation of Anglicanism, in its routine and regular prayers for the state, its support for the vocation to serve the polity, its relationships with the legal, commercial, and political institutions which shape our common life. In an age marked by widespread acknowledgement that an exhausted neo-liberal order needs to be replaced with a richer and 'thicker' vision of the common good, these traditional Anglican practices can help orient us towards a more compelling and satisfying account of the common life.

If Anglicanism is to have a role and place in aiding North Atlantic societies to regain religion, it surely cannot be through means alien to the Anglican experience, ill-suited to and not cohering with the gifts of common prayer, parish, and pastoral generosity. Rather, it will be through a renewed and deepened theological confidence in those traditional practices by which Anglicanism has sought to manifest the "deep ordering to life, culture, and meaning which ultimately leads to God".

His secular friends insist that Scruton continued to be an atheist; that his Christianity was merely cultural Anglicanism. It was that, certainly - but also more. He regained his religion through philosophy, not as a leap of faith, but as an appreciation of a deep ordering to life, culture, and meaning which ultimately leads to God.

Not only is this an excellent description of Scruton's Anglican faith, it also summarises how Anglicanism has traditionally engaged with culture and society. A rich natural theology has underpinned such Anglicanism. Yes, it has been rightly and necessarily qualified by a robust Augustinian recognition of original sin, but this has not been interpreted so as to obscure the meaning of the first article of the Creed, that God is the maker of heaven and earth. In other words, the "deep ordering to life, culture, and meaning which ultimately leads to God" can yet be discerned, is sanctified and celebrated in the Church's life, and is a participation in the life of the Triune God.

Two recent accounts of Anglicanism, given by influential theologians, emphasise how this understanding can continue to shape Anglican life and witness. John Hughes in his 2013 essay 'Anglicanism as Integral Humanism: A de Lubacian Reading of the Church of England' stressed how the traditional Anglican relationship with culture and society - given expression in a range of "very concrete material [pastoral, sacramental, civic] practices" - should be understood not according to "the customary Erastian and latitudinarian lines" but, rather, as a vision of society and culture "flowing from and to him, who is the Alpha and Omega of all things".

Alongside this is the description given by John Milbank of Anglicanism's "hidden coherence":

refusing ... any facile separations between the sacred and the secular or between faith and reason, grace and nature ... sturdily incarnated in land, parish and work, yet sublimely aspiring in its verbal, musical and visual performances.

In both accounts we see how the Anglican way sets before us and draws into the "deep ordering to life, culture and meaning which ultimately leads to God": in the occasional offices sanctifying defining moments at the beginning, in the midst, and at the end of our earthly lives; in the quiet and native beauty of Choral Evensong; in state prayers understanding civic life as proceeding from and oriented to God's life, goodness, and communion; in place, community, and history caught up in the life of the parish church.

The late 20th and early 21st centuries have been marked by a rather catastrophic loss of Anglican in both this vision of the Church's relationship with culture and society, and in the "very concrete material practices" which have embodied it. (Sam Brewitt-Taylor's superb study explains the theological and ideological background this.) In their place, a range of sectarian proposals have been embraced: from Alpha to 'Jesus Movement', all underpinned by post-Christendom theologies which, in the words of Hughes, have abandoned "the possibility of a Christian culture" in "a strange mixture of two theological streams: evangelical Protestantism and liberalism". Such anti-Christendom theologies become self-fulfilling prophecies, undermining and rejecting the very practices which manifest culture and society as called to fulness in Christ, uninterested in these practices manifesting the "deep ordering to life, culture, and meaning which ultimately leads to God".

How might the classically Anglican vision and ethos then be retrieved? Perhaps three suggestions may assist such the beginning of such a conversation.

Firstly, there needs to be a renewal of the historic Anglican vision of natural theology. As Ward notes, Scruton himself significantly contributed to this with his The Face of God (2012) and The Soul of the World (2014), "question[ing] what humanity loses when God is effaced from the human condition". A more confident assertion of the naturalness and goodness of religious belief and the Christian revelation - once commonplace Anglican teaching - is required.

Secondly, a renewed confidence is required in the occasional offices, freed from the constraints placed upon them by liturgical revision, not the least of which constraints is the notion that adult baptism, rather than infant baptism, is the norm. The desire for meaning still marks birth, marriages, and death in a secular age, with humanist celebrants increasingly evident. The idea that the Church should - in a recognition that 'Christendom has gone' - retreat from such defining moments, and not use it occasional offices to unveil a meaning greater and infinitely more humanist than that offered by banal secular alternatives is only to reinforce the assumptions of secularism.

Thirdly, retrieving the civic vocation of Anglicanism, in its routine and regular prayers for the state, its support for the vocation to serve the polity, its relationships with the legal, commercial, and political institutions which shape our common life. In an age marked by widespread acknowledgement that an exhausted neo-liberal order needs to be replaced with a richer and 'thicker' vision of the common good, these traditional Anglican practices can help orient us towards a more compelling and satisfying account of the common life.

If Anglicanism is to have a role and place in aiding North Atlantic societies to regain religion, it surely cannot be through means alien to the Anglican experience, ill-suited to and not cohering with the gifts of common prayer, parish, and pastoral generosity. Rather, it will be through a renewed and deepened theological confidence in those traditional practices by which Anglicanism has sought to manifest the "deep ordering to life, culture, and meaning which ultimately leads to God".

Full disclosure: Roman Catholic who lurks on this blog because he loves so much about Anglicanism.

ReplyDeleteI have loved your writing and found it quite thought provoking. Not to cause a flame war, but I couldn't help but notice the image of the infant baptism with a female priest. The admission of women to the priesthood is something that has always kept me away from the Anglican Church, because of (IMO) biblical, historical and traditional arguments. Would you at some point be willing to write an article about female priests and especially bishops? The admission of women to these orders strikes me as something that really ends the claim of a Church which follows the apostolic faith.

Robert, many thanks for your comment and thank you for reading the blog.

DeleteI will take up your invitation to address in a post the issue of the ordination of women as priests and bishops. I will say at this stage that I live and minister in a Church which does ordain women as priests and bishops, I do so happily and willingly, that I receive the ministrations of women who are priests, and would do likewise with a bishop who is a woman. That said, my theological reasoning in doing so is rather different from many supporters of the ordination of women.

I will post on the topic next week. Thank you for the idea!

Brian.