"The Protestant Episcopal Communion in Scotland": St. Andrew's Day thoughts on Scottish Episcopalianism and the Old High tradition

That unfortunate and ill-advised measure [i.e. the '45], in which, so far as I know and believe, the clergy of this Church had no general nor active concern whatever, caused them to be immediately silenced through the whole land. In Edinburgh, where their chapels were numerous and their congregations respectable, they were shut by authority, and the clergy compelled to silence, under a penalty rigidly exacted or enforced ...

After the accession of George the Third, they [i.e. the penal laws] were seldom enforced, and never with the rigour of the previous reign. They were still in force, however, and any zealot or local enemy might subject the episcopal minister to much annoyance and inconvenience, and even to the utmost penalty, of which some instances occurred even then ...

Though the active persecution had generally ceased, as I have stated, yet the consequences of that persecution were most severely felt in every part of the Church at the time when Alexander Jolly was admitted into Deacons' Orders.

The contrast with the context in which the Church of England ministered was, of course, incredibly stark. It is this which makes particularly significant Jolly's account of Scottish Episcopalian liturgy in his 1826 A Friendly Address to the Episcopalians of Scotland on Baptismal Regeneration. This account of Morning Prayer, the Litany, Ante-Communion, and the Holy Communion could have been offered by any divine in the Old High tradition in England, Ireland, Canada, or the United States.

For example, consider Jolly on the absolution at Morning and Evening Prayer, a characteristic Old High understanding of the efficacy of this absolution:

Blessed as we are with a Liturgy, the Book of Common Prayer, which is truly scriptural, and primitive in its language and doctrine ... The daily service, morning and evening, calls forth our faith, elevates our hope, and enflames our love or charity, for the increase of which, with all that is truly good, we incessantly pray, beginning with the exercise of repentance; for if we regard iniquity in our hearts; the Lord will not hear our prayers. The confession of our sins is so general, that the most advanced Christian will ever need to say it with a feeling sense of his imperfections and daily trespasses; and yet so contrived, that every particular sinner will find room to recollect his predominant disorders, with their aggravations. And while it fervently excites us, under a sense of our miseries, to cry for mercy, it fixes our faith and hope upon those promises made in Christ Jesus our Lord. At the same time, me, it puts us in mind of and earnestly begs grace that we monft the whole duty of man, to God, our neighbour, and our selves in the exercise of a godly, righteous, and sober life, to the glory of his holy name. The absolution holds out the hope, and gives the sacerdotal assurance of God's pardon, but only if we truly repent, and unfeignedly believe His holy Gospel, we have confidence to call upon him as our reconciled Father ...

Here you see, on the very threshold of the Church, the Gospel meets you, holding out to you repentance and remission of sins, as the Divine Author of it, after his resurrection, gave the sum of those glad tidings, which the word Gospel signifies, commanding them to be preached in his name among all nations; confirming the word of the Angel at his birth, I bring you good & tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people not to a select few, but to all people, who, upon hearing shall give ear and faithfully receive the gracious proclamation of pardon and peace, upon true repentance. It is thus, in truly evangelical style, that the Church leads us into her house and service.

Likewise, Jolly's praise for the Litany was typical of the Old High tradition:

On Sunday, Wednesday, and Friday, the Litany is added to the Morning Service ... The Litany, also, is admirably evangelical, as easily might be shown, were this the place to make remarks upon it. Most moving and melting is this humble supplication; and no heart that has any pious feeling of devotion can remain cold or unaffected in the solemn performance of it.

While Jolly, like many other Old High bishops, encouraged a more frequent reception of the holy Sacrament, he did regard the Ante-Communion to be a useful act and an integral part of the liturgy:

Still, however, the Church, to bear testimony to the duty, and send, as it were, a wish after its restoration [i.e. more frequent reception], as she does on Ash Wednesday for that of the primitive Penitential discipline, orders a part of the solemn service, every Sunday and holy day to be read at the Altar, by her express Rubric: "Upon the Sundays and other holy days (if there be no Communion) shall be said all that is appointed at the Communion, until the end of ( the General Prayer for the whole Church". Hence, devout people, even in this lame part of the Office, including the Eucharistic Intercessional Prayer for the whole Church, have an opportunity of uniting in heart and desire with the celebration, wherever it is duly made, and communicating in will, when they cannot in act: leading every day a holy life, watching and praying always that they may be continually prepared, and embracing every opportunity of receiving ...

In the previous part of the Altar Service - the divine word in the Epistle and Gospel leading the way - the Sermon is introduced. The Creed, the Lord's Prayer, and the Ten Commandments, going before, and containing the divine virtues of faith, hope, and charity, open an inexhaustible fund of doctrine, according to the summary form of sound words, to which every sound preacher will confine himself; holding them fast, and teaching no other doctrine than that which is from Scripture contained in the Liturgy - a storehouse of sound doctrine as well as sublime devotion, embracing every point of faith and practice.

On the holy Sacrament itself, Jolly evoked Hooker's description of the relationship between Baptism and Eucharist, used the traditional Old High language of commemorative sacrifice, and echoed 1662 ("the innumerable benefits which by his precious blood-shedding he hath obtained to us"), providing a conventional Old High sacramental understanding:

After the Litany, follows the most sublimely exalted Office of all, the service of the Altar, commemorative of the sacrifice of the death of Christ, pleading his merits for acceptance, that we may receive the benefits which He, by His precious blood-shedding, hath obtained to us. For hereby is perpetually nourished that divine life first begun by our regeneration in Baptism, sealed by Confirmation. These are the beginning of the spiritual life, which can be received once only, the foundation which cannot be laid again. But the principle of life, imparted by the new birth, or regeneration of Baptism, strengthened by Confirmation, is to be continually supported and preserved by the heavenly food, the bread of life, answering to the tree of life in Paradise; by the devout receiving of which, our claim is maintained to that glorious immortality in body as well as soul, which we lost in Adam, but which Christ re-purchased for us, by His death in our stead, and now consigns to us by divinely instituted Sacraments.

Noteworthy is the absence - in a work addressed to Scottish Episcopalians - of any reference to those distinctives of the Scottish Communion Office, the oblation and invocation. This is suggestive that they perhaps did not bear the weight of meaning later suggested by those who looked to the Scottish rite as an example of a supposedly higher eucharistic theology than found elsewhere in the pre-1833 Old High tradition.

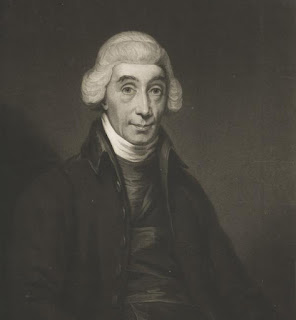

There was, of course, no different Episcopalian 'stream' of eucharistic theology. Jolly points to an understanding of liturgy and piety which was no different to Old High teaching elsewhere. The title page of his popular 1828 work, Observations upon the several Sunday Services and principal Holydays prescribed by the Liturgy throughout the Year, referred to him as "one of the bishops of the Protestant Episcopal communion in Scotland". His account of the liturgy was no different than those given by Old High bishops and divines in the Protestant Episcopal communions of England and Ireland, in Canada, and the United States. The particular circumstances of the Scottish Episcopalian relationship with the state, their earlier 18th century dynastic allegiances, even the characteristics of the Eucharistic rite of the 'wee bookies' did not produce an Episcopalian 'stream' which differed from Protestant Episcopalians elsewhere. Contrary to later purist fantasies of Scottish Non-jurors, fashionable amongst some Tractarians, Jolly exemplifies how Scottish Episcopalians took their place, via the common and often dominant Old High vision, amongst the Protestant Episcopal communions in these Islands and across the Atlantic.

Comments

Post a Comment