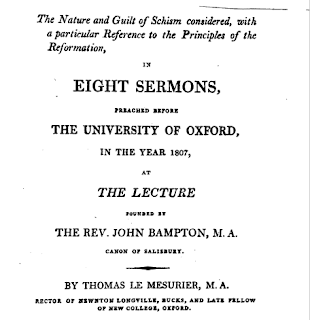

In the fourth of his 1807 Bampton Lectures,

On the Nature and Guilt of Schism, Le Mesurier continues with his exposition of how authority functioned amongst the patristic churches. This was the "

example of the primitive church" to which the Church of England returned at the Reformation, in which (to use the words of Article XXXIV) "every particular or national church hath authority" to order its affairs:

In all this, clearly, there is nothing like what can be properly called jurisdiction in one church or bishop over another: nothing but what I have stated, that when any evils were to be resisted, or any point of doctrine or of discipline to be ascertained, those bishops who could do so, met together and declared their sentiments. Those sentiments were communicated to the other churches, and were adopted and observed according to their apparent reasonableness, and the weight of character which belonged to those from whom they came. Nothing was pretended to but that general and mutual superintendance over each other which is exercised by all bodies which are united and co- operating together in any common cause.

If in the case of Paul of Samosata, the sentence was accompanied with deprivation, we must recollect that the council was held at Antioch itself, in the very city of which he was bishop, and must have been so held with the consent of the clergy and people, as well as of the bishops who composed it; that is, in fact, of all those whose concurrence could be required in any election to the see, and in whom or some of whom, must have resided the power of removing individuals who should have so corrupted the doctrine as to be unfit any longer to preside over the church.

Still the different churches continued independent of each other and equal in authority.

While Le Mesurier's account of the 269AD Synod of Antioch deposing Paul of Samosata for heresy is (to say the very least) unconvincing, it does nevertheless illustrate his wider point. This emergency action was by churches in "the neighboring cities and nations", as the epistle (contained in

Eusebius) sent from the Synod declared: it was, in other words, an action by those churches in the geographical vicinity of Antioch, what we might describe as a 'province'. The confusions emerging from the Synod - Paul continuing to claim the See, the Synod's rejection of the term

homoousios (used by Paul!), and the ultimate reliance on the civil authority, the pagan emperor Aurelian - rather dramatically emphasise that there was no obvious, ordinary jurisdiction exercised by bishops over other churches.

That Aurelian decided that the See of Antioch, to quote Eusebius, "be given to those to whom the bishops of Italy and of the city of Rome should adjudge it" was not, as is sometimes fondly suggested, a recognition by the churches of Roman primacy. It was, rather, a decision driven by Aurelian's imperial vision of restoring the empire. Such an action by the emperor would not have been necessary, of course, if other churches did indeed have jurisdiction over other particular churches.

Not mentioned by Le Mesurier, but worth noting, is that the Synod of Antioch, rejecting homoousios in its condemnation of Paul of Samosata's teaching, a point often invoked by later anti-Nicene theologies, also exemplifies the truth that synods and councils "may err, and sometimes have erred".

And one final point. The epistle sent by the Synod of Antioch to other churches, informing them that Domnus had been appointed bishop in place of Paul, described the new bishop as "a son of the blessed Demetrianus, who formerly presided in a distinguished manner over the same parish". We might say that here was another way in which the Church of England followed the example of the Primitive Church.

Comments

Post a Comment