'Moderation, learning, usefulness, piety': an Old High Church alternative to 'Simpler, humbler, bolder'

As a number of commentators have pointed out, this vision sits uneasily beside classical Anglican (and not merely CofE) forms, commitments, and virtues. Above all, it might imply what we might term a 'Hauerwasian turn': a turn away from an incarnational commitment as a national church to a sectarian congregationalism. At heart, it appears to be a decision to embrace a very different theology of the Church, of mission, and of culture.

What, then, might a more classically Anglican alternative to 'simpler, humbler, bolder' look like? I turn to a perhaps rather surprising source, an 1828 Charge given by Christopher Bethell, then Bishop of Gloucester. Bethell was one of those 'High and Dry' bishops later resented (and misrepresented) by the Tractarians. In his 1828 Charge, Bethell referred to "the pre-eminent reputation of our National Church for moderation, learning, usefulness, and piety". Is it possible that this description offered by an Old High Church bishop of the late Georgian era offers a more realistic and meaningful vision for contemporary Anglicanism than 'simpler, humbler, bolder'?

Moderation

The historic Anglican theological and social critique of 'enthusiasm' and sectarianism is at the core of this moderation. It is deeply rooted in Hooker's reaffirmation of the Thomist conviction that grace does not destroy nature: that the relationships and obligations of domestic, communal, and national life are not undermined by Christianity but, rather, are blessed and received with thanksgiving. As C.S. Lewis said of Hooker's vision:

God is unspeakably transcendent; but also unspeakably immanent. It is this conviction which enables Hooker, with no anxiety, to resist any inaccurate claim that is made for revelation against reason, Grace against Nature, the spiritual against the secular. We must not honour even heavenly things with compliments that are not quite true: 'though it seem an honour, it is an injury' (II.8.7). All good things, reason as well as revelation, Nature as well as Grace, the commonwealth as well as the Church, are equally, though diversely, 'of God'.

This finds particular expression in the commitment of parish and cathedral to communal flourishing and civic peace. In the post-9/11 cultural and geopolitical context, accentuated by popular reception of the New Atheist critique of religion as 'a Bad Thing', such moderation can challenge the narratives that portray religion as, in the words of Linda Woodhead, "a 'toxic brand', prejudiced and illiberal at best, divisive and destructive at worst".

In his essay 'Anglicanism as Integral Humanism', John Hughes pointed to Rowan Williams' comment on the poetry of George Herbert: "a rejection of the view that 'God can only be honoured by a kind of dishonouring of the human'". This rejection, said Hughes, is to be found "in a particular piety and sensibility which could be seen as particularly Anglican: a sense of all creation being in God and God being in all creation, through Christ". Such 'moderation' offers an alternative to a retreat into a sectarian enthusiasm which would confirm cultural suspicions of religion in general and Christianity in particular.

Learning

Students at Oxford, Cambridge and Durham are twice as likely to worship on a Sunday as the general population, according to Church of England data (The Times, 28th March 2018).

Mindful of the above statistic, one might have thought that any 'vision for the Church of England in the 2020s' would have given considerable thought to what could be learnt from such college chapels in Oxford, Cambridge and Durham, integrating the life of the mind with Christian prayer and worship in a manner which attracts and encourages participation in the Church's life. 'Bolder, simpler, humbler', however, appears to have decided otherwise.

There is, of course, a long and noble history of Christianity establishing and sustaining centres of learning and practices of learning. This has, over the centuries, been recognised as contributing to the good and flourishing of the community and polity. It has also encouraged a reverence for reason and philosophical inquiry, and a celebration of the truth discerned in and through 'natural revelation'. As Hooker said of "Egyptian and Chaldean wisdom mathematical ... or that natural, moral, and civil wisdom of the Greeks":

God himself, who being that light which none can approach unto, hath sent out these lights whereof we are capable, even as so many sparkles resembling the bright fountain from which they rise (LEP III.8.9).

Anglicanism outside of England established centres of learning: for example, Trinity College Dublin, King's College, Sewanee. While, of course, many such institutions are now entirely secular, their existence is witness to Anglicanism's historic commitment to promote institutions of learning. In differing forms and to different extents, Anglican Churches often maintain schools or have a presence in schools, another sign of that historic Christian commitment to nurturing the pursuit of wisdom and encouraging the right use of reason. Again, questions can be asked about the character of such schools and how this coheres with the Church's life and mission. Nevertheless, the existence of such schools also witnesses to that historic commitment to nurture lives in the ways of wisdom and reason.

In The Love of Wisdom, Andrew Davison has described the theological significance of this commitment, and of these institutions and practices:

its scope is nothing less than the whole of human life: all that proceeds from human reason and desire, imagination and creativity. Its goal is not only that our worship may be 'rational' (Rom. 12.1) but also that our reason may be worshipful, forever rejoicing in God as reason's origin and goal.

This is suggestive of the attractiveness of such commitment, institutions, and practices, rooting wisdom and reason - and thus human flourishing - not in an uncertain and unstable utilitarianism or pragmatism but in the Source of life and being. It is, in other words, integral to Anglicanism offering a vision of human flourishing.

Usefulness

I mean, it just seems to me as if the treasure of Christianity, among many others, is that it does sort of tell us how we should live in the world, and for our benefit, in order to feel abundance, you know?

The Anglican tradition has traditionally sought to provide an answer to Marilynne Robinson's words. The Book of Homilies in some ways exemplifies this, with homilies addressing attitudes towards food, clothing, and labour, and obligations in matrimony, community, and polity. In the Communion Office, communal obligations are a central feature: in the second table of the Decalogue, the receiving of "alms for the Poor", the prayer for the common life of the polity, and the call to be "in love and charity with your neighbours".

Anglicanism has a long history of placing on emphasis on teaching and catechesis which nurtured and sustained communal obligations and civic peace. Even the much maligned 'passive obedience and non-resistance' should be understood as seeking to ensure civic peace in the face of sectarian tensions and how the breakdown of allegiance threatened the gift of being "godly and quietly governed". Another expression of this commitment was to be found in the contribution of Anglican figures and social teaching to the post-1945 welfare state in the United Kingdom, a similar attempt to secure communal peace and well-being, what Sam Brewitt-Taylor has termed a "'late Christendom' vision of modernity".

Part of this wider social vision has been, of course, a recognition that Christian Faith is lived out in the ordinary, routine of parish, domestic, neighbourly, and commercial obligations: attending parish worship on Sunday, supporting the parish, attentiveness to domestic duties, being a good neighbour, being "true and just in all my dealings". This supplies an attractive alternative to what Alison Milbank recently termed "materialism without the sacred, individualism without roots": not a rejection of materialism, but its sanctification; not a rejection of individualism in favour of collectivism, but a recognition that the communal is essential for our flourishing and well-being.

To borrow words from Andrew Davison, this is to give an account of Christian faith and life that is "attractive, sane and wise" - surely an evangelistic imperative in a cultural context in which the search for such rhythms and patterns of life is widespread.

Piety

Whereas the 'simpler, humbler, bolder' trio seeks the creation "a Church of missionary disciples", the Old High Church quad seeks something that is, well, humbler. Rather than a boldly sectarian vision, the Old High Church quad would be committed to a (forgive the term) fresh expression of Anglicanism's commitment to pastoral generosity as a means of enabling participation in life in Christ. How could Anglican piety nurture piety in a 'secular age'? Perhaps it can do so around three hubs.

Firstly, a confident and thoughtful emphasis on and administration of the Occasional Offices. At key moments, defining moments in life, the Occasional Offices offer meaning - transcendent and immanent - when meaning is often sought. This will mean a recovery of Christening (Sarah Lawrence's A Rite on the Edge is essential reading on this), a renewed sense that the Solemnization of Matrimony celebrates a means of human flourishing (to be somewhat controversial, less sacramental, more a 'state of life allowed in the Scriptures'), and a confident understanding that the Burial Rite offers a meaning in the face of death infinitely greater than whatever a humanist officiant can possibly say.

Secondly, building on those festivals which have a popular resonance: Christmas and Easter, and (in the UK) Harvest and Remembrance. Rather than a resentful, dismissive approach to how popular religion approaches these festivals, there needs to be a commitment to resonant, appropriate liturgy and teaching which seeks to enable a creedal Christian vision to take root in the hearts and minds of occasional worshippers.

Thirdly, and related to the above two hubs, there should be a new recognition of the significance of non-eucharistic liturgies. The Parish Communion movement, whatever successes it may have had in terms of the Church's eucharistic self-understanding, has been a failure in terms of providing a meaningful connection between the wider culture and the Church's worship. The success of Choral Evensong in the English context (and it is possible to point to examples of the resonance of Choral Evensong and Choral Compline outside England), is suggestive of the need for non-Eucharistic liturgies which enable participation by the occasional worshipper, those on the periphery, and those exploring. In the words of a 2016 report on the popularity of Choral Evensong in Oxbridge chapels:

College chaplains have seen a steady but noticeable increase in attendances at the early evening services which combine contemplative music with the 16th Century language of the Book of Common Prayer ... Chaplains say the mix of music, silence and centuries-old language appears to have taken on a new appeal for a generation more used to instant and constant communications, often conducted in 140 characters rather than the phrases of Cranmer.

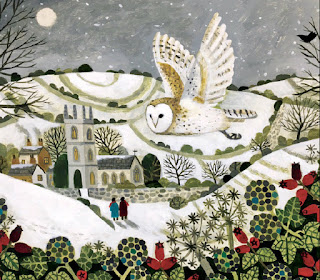

(The painting is by contemporary artist Vanessa Bowman. It reminds us that even in a wintry landscape, there are Advent riches to be nurtured, cherished, and celebrated.)

Comments

Post a Comment