Looking in a northerly direction: the Protestantism of 1662

My emphasis is on the similarities between the rites and ceremonies of 1662 and those in the Churches of the northern Lutheran kingdoms, pointing to "a reformed catholic vision, shared with the Churches of the Augsburg Confession, of liturgical and sacramental life".

---

As previously stated, to describe the Book of Common Prayer as Protestant inevitably provokes the question “what sort of Protestantism?” The “Admonition to the Parliament” suggests an answer with its description of Prayer Book liturgies:

Holydayes ascribed to saincts, prescript seruices for them, kneeling at communion, wafer cakes for theyr breade when they minister it, surplesse and coape to do it in.

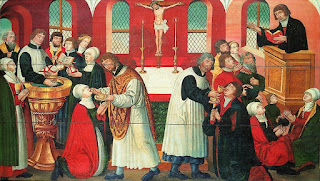

For the authors of the Admonition, such a form of worship was, of course, Roman. What the Admonition overlooks – and what Conformist writers regularly emphasized – was that this form of worship was also to be seen elsewhere in Protestant Europe, in the Lutheran kingdoms of Scandinavia and the Lutheran principalities of Germany. The priest in surplice, administering the Holy Sacrament to communicants kneeling, the words of administration addressed to each communicant, with the traditional collect, epistle, and gospel (in Sparrow’s words, “the use of them in the Christian Church was ancient”) having been read: this was a scene much more reminiscent of worship in the Lutheran kingdoms than the Reformed states. When the Conformist apologist Thomas Rogers defended kneeling to receive the Holy Sacrament, he pointed to how this was the practice of the churches of “Saxony, Denmark, and many in Germany.”

It was also the case with the scene at Holy Baptism. The priest in surplice, a version of Luther’s “Flood Prayer,” the blessing of the water in the font (in 1662), the use of the sign of the Cross on the baptized: this was to be seen not in the Reformed churches of the Netherlands, France, or Switzerland but in the Lutheran kingdoms. What is more, the explicit declaration of the Book of Common Prayer’s Baptismal rite that “this Child is regenerate,” and the prayer of thanksgiving that “it hath pleased thee to regenerate this Infant,” is at one with the affirmation of the Lutheran 1592 Saxon Visitation Articles that “Baptism is the bath of regeneration,” contrasting with the depiction of the Reformed view that “Baptism is an external washing of water” which “does not work nor confer regeneration.”

The Prayer Book’s provision for “Receiving into the Congregation Children which have been privately Baptized” was also a feature shared with Lutherans and rejected by Reformed churches. Thus the Saxon Visitation articles articulate and condemn the Reformed error of rejecting such provision:

That salvation doth not depend on Baptism, and therefore in cases of necessity should not be required in the Church; but when the ordinary minister of the Church is wanting, the infant should be permitted to die without Baptism.

Private Baptism featured in the 1618 Articles of Perth, by which James VI/I sought to bring the Church of Scotland into greater conformity with the Church of England. (James had reintroduced episcopacy to Scotland in 1610.) The articles were condemned by Reformed opponents for introducing “idolatrous, superstitious, and ridiculous ceremonies.” The rejection of private Baptism was based on the assertion – which had been condemned in the Saxon Visitation Articles – that “there is no precept requiring baptisme, when it cannot be had orderly.” It is noteworthy that each of the Articles of Perth called for Prayer Book practices shared with the Lutheran churches: kneeling to receive the holy Sacrament; administration of the Eucharist to the sick in private; private administration of Holy Baptism when necessary; the rite of Confirmation; and the observance of festivals.

In his defense of the 1662 settlement, the Anglican apologist John Durel declared that the polity and liturgy of the Church of England and the Churches of the Augsburg Confession were “the very same.”

As for the public Worship of God, they have all of them set Forms of Prayer, not one excepted … They observe Holy days; they have set Times for fasting; they have very magnificent and stately Buildings very richly adorned for their Churches. They sing not only Psalms, but many Hymns and spiritual songs … And they sing them with Organs and other instruments of Music. They sing Anthems in the same manner that we do. In many places they wear Surplices and other Church-Ornaments. They use the Cross in Baptism; they receive the Communion kneeling. In fine, they have Conformity with us in all Rites of Divine Worship.

The rites and ceremonies of the Prayer Book were indeed Protestant: but it was the Protestantism of the northern Lutheran kingdoms, not of the Reformed states.

Comments

Post a Comment