"It is a sin not to adore when we receive this Sacrament": why adoration is integral to Anglican eucharistic practice

I never understand why folks insist that the Eucharist is meant for eating and not for adoring. Not because it's not meant for eating. It is. That's communion. But why can't the two go together? It's my grand gripe about much sacramental theology today.

What immediately caught my attention was the question: "why can't the two go together?" A classically Anglican response would be to say 'Yes, communion and adoration must go together and cannot be separated'.

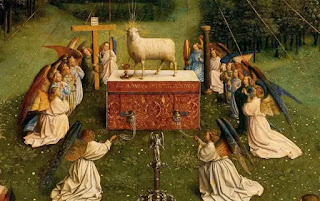

A key text from Augustine appears in the writings of Andrewes, Sparrow, and Taylor on the subject. In his homily on Psalm 98, Augustine said:He ... gave that very flesh to us to eat for our salvation; and no one eats that flesh, unless he has first worshipped.

For Sparrow, the expression of such adoration of Christ as we partake of Him in the holy Sacrament is that we kneel to receive:

It is to be given to the people kneeling. For a sin it is not to adore when we receive this Sacrament, Aug. in Psal. 98.

Andrewes likewise points to Augustine's words:

which, I trust, no Christian man will ever refuse to do; that is, to adore the flesh of Christ.

For Taylor, Augustine's exhortation is similarly crucial:

concerning the action of adoration, this I am to say, that it is a fit address in the day of solemnity, with a ''sursum corda,' with 'our hearts lift up' to heaven, where Christ sits (we are sure) at the right hand of the Father, for ... said S. Austin; "no man eats Christ's body worthily, but he that first adores Christ".

We must, therefore, adore Christ as we feed on Him in the holy Eucharist: this is integral to our reception of the Sacrament. Reception and adoration cannot be separated.

This robust emphasis is, of course, maintained within the Reformation emphasis (shared with Orthodoxy) that the consecrated elements are not themselves to be adored. Andrewes illustrates this by drawing attention to further words of Augustine's homily on Psalm 98:

[The Lord] instructed them, and says unto them, "It is the Spirit that quickens, but the flesh profits nothing; the words that I have spoken unto you, they are spirit, and they are life". Understand spiritually what I have said; you are not to eat this body which you see; nor to drink that blood which they who will crucify Me shall pour forth. I have commended unto you a certain mystery; spiritually understood, it will quicken.

It is not that which is seen - bread and wine - which is to be adored, but the One who is unseen, the Crucified and Ascended Lord, of whom we partake spiritually:

Reception and adoration must 'go together' because Christ is "sacramentally and really (not feignedly) present". And because this real, sacramental presence is necessarily spiritual, it is Christ Himself who is to be adored, not the signs "exhibiting" His presence. In other words, not adoring the bread and wine is not because of a 'low' view of the Sacrament. Rather, we do not adore the bread and wine precisely because Christ is present in the holy Eucharist.

This particularly emphasises the significance of kneeling to receive in Anglican Eucharistic practice. We kneel because Christ is "really present", giving Himself to us as we partake of the Sacrament. We kneel because we adore Christ Himself. To remove kneeling is to disorder both Eucharistic practice and belief in the Anglican tradition, undermining and obscuring the need for adoration when we receive. In the words of Taylor:

And thus we affirm Christ's body to be present in the sacrament: not only in type or figure, but in blessing and real effect.

Comments

Post a Comment