'Against Puritanism and Popery': Laudian continuity with earlier Conformity

Thus in July 1624 one of the most uninhibited spokesmen of the movement, Richard Montague, said that he sought a Church of England that would 'stand in the gapp against Puritanisme and Popery, the Scilla and Charybdis of antient piety'. This was the beginning of the via media discussion, which would have a major future in the Anglican tradition.

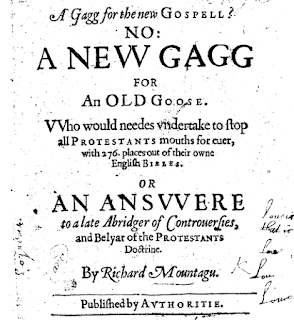

This, to say the least, seriously misunderstands Laudianism. To begin with, Montague's famous A New Gagg (1624) was, as the text makes abundantly clear throughout, an explicit defence of Protestantism:

Against Protestants your Gag is directed, not Puritans: and yet all your addresses, well-neer, are against Puritan Positions, malitiously imputed to Protestants.

The "gapp against Puritanisme and Popery" was Protestantism precisely because Puritanism was not the magisterial Protestantism of the reformed Church of England. Montague's stance here was anything but an innovation. He was merely rehearsing a very well established Conformist apologetic.

It is a stance evident throughout Hooker's Laws. The Preface expounds "the manifold dangerous events" which would ensue if the Puritan agitation achieved its purpose of overthrowing "the present form of Church government which the laws of this land have established". At the conclusion of Book IV, Hooker contrasts how the Church of England was reformed with other forms of Reformation:

both kinds of reformation; as well this moderate kind which the church of England hath taken, as that other more extreme and rigorous which certain churches elsewhere have better liked.

The Church of Elizabeth stands in "the gapp" between a Church unreformed and Churches whose Reformation has been "extreme".

The same contrast is evident in Bancroft's famous sermon, in which the visions of the Puritan Cartwright and the Roman apologist Harding were contrasted with the ecclesia Anglicana under the Royal Supremacy, the means of ensuring the good ordering of church and commonwealth:

And they affirme, that no civill magistrate hath preeminence by ordinary authority, either to determine of church causes, or to make ecclesiasticall orders and ceremonies. That no civill magistrate hath such authoritie, as that without his consent it should not be lawfull for ecclesiasticall persons to make and publish church orders. That, 'They which are no Elders of the church, have nothing to do with the government of the church'. And whereas Master Harding saith, that the office of a king in it selfe is one everie where, not onely among the Christian princes, but also among the heathen: and thereupon concludeth, that a Christian prince hath no more to do in deciding of Church matters, or in making ceremonies and orders for the Church, than hath a heathen: Master Cartwright alloweth of his judgement, and doth expressely affirme, that he is of the same opinion, professing his mislike of those who teach another right of a Christian, and of a prophane magistrate.

In the face of the Puritan agitation, Bancroft declared, "The Papists did never deale with more egernes against us than these men do now". Against both he set forth the case of the ecclesia Anglicana:

The doctrine of the church of England, is pure and holie: the government thereof, both in respect of hir majestie, and of our Bishops is lawfull and godlie: the booke of common praier containeth nothing in it contrarie to the word of God.

In Hooker and Bancroft, then, we see leading apologists for and defenders of Elizabethan Conformity positioning the Church of England in "the gapp" between the unreformed Church of Rome and the enthusiasts for extreme reform.

This was also to be seen in that epitome of Jacobean Conformity, John Donne. In a 1616 sermon on the anniversary of the accession of James I, Donne celebrated the monarch's commitment to the ecclesia Anglicana:

Next let us pour out our thanks to God, that in his entrance he was beholden to no by-religion. The papists could not make him place any hopes upon them, nor the puritans make him entertain any fears from them; but his God and our God; as he brought him via lactea, by the sweet way of peace, that flows with milk and honey.

Not only was Donne here standing in continuity with Elizabethan Conformist apologetics, he was also echoing James himself. The Book of Sports issued by James in 1618 had stood against both "papists" and "Puritans", the former alleging "no honest mirth or recreation is lawful or tolerable in our religion", the latter "prohibiting and unlawful punishing of our good people for using their lawful recreations and honest exercises upon Sundays, and other holy days".

The same contrast was also to be found in an enduring achievement of James, the Authorized Version of the Scriptures. In 'The Translators to the Reader' we read:

we have on the one side avoided the scrupulosity of the Puritans, who leave the old Ecclesiastical words, and betake them to other, as when they put Washing for Baptism, and Congregation instead of Church: as also on the other side we have shunned the obscurity of the Papists, in their Azimes, Tunike, Rational, Holocausts, Praepuce, Pasche, and a number of such like, whereof their late Translation is full, and that of purpose to darken the sense, that since they must needs translate the Bible, yet by the language thereof, it may be kept from being understood.

We might be hard pushed to find a more significant statement of the conviction that the Church of England - for, of course, the Authorized Version was designed to be a liturgical text, incorporated in the Book of Common Prayer - stood "in the gapp against Puritanisme and Popery".

It is in George Herbert's 'The British Church' that this understanding of the ecclesia Anglicana finds poetic expression. The Church of England, "A fine aspect in fit array, Neither too mean nor yet too gay" is contrasted with the Church on the hills (Rome) and "in the valley" (those Churches which experienced less moderate Reformation:

She on the hills which wantonly

Allureth all, in hope to be

By her preferr'd,

Hath kiss'd so long her painted shrines,

That ev'n her face by kissing shines,

For her reward.

She in the valley is so shy

Of dressing, that her hair doth lie

About her ears;

While she avoids her neighbour's pride,

She wholly goes on th' other side,

And nothing wears.

By contrast, Herbert celebrates the Church of England for keeping "The mean" between these two. A glorious example of this in ordinary parish life is found in the 1632 funeral sermon for the Rector of Herbert's home parish, St Martins-in-the-Fields:

a true son of the Church of England, I mean a true Protestant; he was as far from popish superstition, as factious singularity, nor more addicted to the conclave of Rome than addicted to the parlour of Amsterdam (quoted in Drury's Music at Midnight).

The evidence, then, is rather overwhelming that Montague's statement, far from suggesting a rupture with the identity and thought of earlier Conformity, stood in obvious continuity with it. He was merely restating what apologists for Elizabethan and Jacobean Conformity had repeatedly declared. Which brings us to a key point in understanding Laudianism and the disputes of the 1630s. It was the Puritan agitation which sought to undermine the Elizabethan Settlement, upheld by Jacobean and Caroline Church. It was the Puritan agitation which desired to overthrow Herbert's "mean" and embrace what Hooker had warned against, the measures which came to pass in the 1640s when episcopacy, Prayer Book, and modest ceremonies were prohibited. It was, in other words, the Laudians who stood in "the gapp", defending the "mean", the "moderate" settlement of Elizabeth, against the "extreme and rigorous".

Your statement "unreformed Church of Rome and the enthusiasts for extreme reform", with the rest of the summary, is as if you are looking at Old High Church from the fraudulent perspective that Anglo-Catholics are, with the other fraud - that is, Puritans who made better Presbyterians.

ReplyDeleteI have to confess to being rather confused by your comment. I was describing how Hooker portrays the Conformity of the Elizabethan Settlement. This portrayal was widely repeated by Conformists and is routinely recognised by scholarship. Referring to Anglo-catholics in such a context would be absurd and nonsensical. If, on the other hand, you are identifying Anglo-catholics with how Hookerian Conformists viewed the unreformed Roman Church, that is quite a different matter - but it is not what I am addressing in this post.

Delete