The resonance and relevance of Cranmerian Morning and Evening Prayer

That we are good and rational and, most importantly today, have a right to pursue these ends is taken for granted. The problem is that ... it isn’t true.

A cursory look at the history of humanity should be more than enough. Yet we have had people who read history at university at the forefront of government for a number of years and remain stuck in a rut around human nature. How many public policy mistakes have been the result of the basic miscalculation that people are good and rational and will behave accordingly? From the right to buy scheme to Covid marshals, the last 40 odd years of British politics are littered with ideas that were presented as sensible in the abstract until the knotty reality of human nature got involved.

... the philosophy of our governing, commenting and culturally dominant, classes is the problem here: it’s very easy to believe people are fundamentally sensible and good and trustworthy when you believe yourself to be so as well.

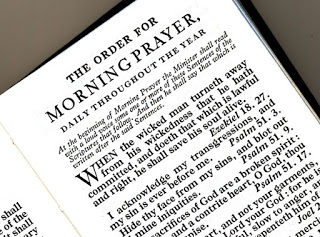

What is particularly striking about this insightful recognition of how a foolish, ahistorical view of human nature has disordered the public realm is that, at the same era, Anglican liturgical revision has significantly reduced the penitential character in many liturgies. We now have a few, brief kyries at the beginning of Parish Communion in place of the robust realism of the Confession at Mattins:

We have left undone those things which we ought to have done, And we have done those things which we ought not to have done, And there is no health in us: But thou, O Lord, have mercy upon us miserable offenders ...

Liturgical revisers of the late 20th century, of course, condemned this as irretrievably grim. That, however, was a view shaped by the assumptions underpinning the rather safe life of white, privileged Anglo-Saxon liturgists in the 1980s. What turned out to be grim (who could have guessed?) was a sunny, breezily optimistic view of human nature. Less than 5 minutes online rather easily confirms that such an optimistic view is wildly deluded.

What is more, as Fergus Butler-Gallie points out, the robustly realistic view of human nature in the Prayer Book general Confession "leads to much more laughing, loving and, well, living than believing that such pursuits are moral goods in, and of, themselves": it can underpin much more resilient and forgiving relationships and communities precisely because it does not share a deluded vision that they are, that we are, that I am good and rational.

The second article appeared in the New Statesman, in which writer Lamorna Ash explored what might lead 20-something Londoners to embrace Christianity through (reading between the lines) a HTB Alpha course. Her view of the course and its brittle, flimsy presentation of the Christian faith is important reading but what particularly caught my attention was how this contrasted with her closing paragraph:

I’ve started reading the Psalms on my own, first thing in the mornings. I find myself moved by their plangent, first-person entreaty. “O my God, I cry out by day, but you do not answer, by night” (Psalm 22), “O God, why have you rejected us for ever?” (Psalm 74). At its most human, most desperate pitch, I come closest to knowing what faith might be – the desire to unblock my ears and be ready to hear it, even if I’ll never truly understand.

The Psalter, of course, is a central part of the Cranmerian Office. Drop into Choral Evensong in a cathedral or college chapel, or listen to the service on BCC Radio 3 on Wednesdays, and you will (hopefully) hear the psalms appointed for the day in the Prayer Book's monthly cycle.

In his exploration of Choral Evensong - Lighten Our Darkness: Discovering and celebrating Choral Evensong (2021) - Simon Reynolds notes how the Psalter gathers up all human experience:

the Psalter encompasses the contrasting experience of praise and lament, hope and despair, tragedy and triumph, exile and home-coming, grief and delight.

Reynolds goes on to quote Brueggemann's view that "the Psalms can be approached as a body of poetic wisdom". We see something of this in Ash's words, a reminder of why the Psalter at the heart of Mattins and Evensong can have significant contemporary resonance, unsettling secular assumptions about scripture, and contrasting with brittle, flattened presentations of Christianity.

The third article was by US evangelicals Dru Johnson and Celia Durgin in Christianity Today, asking 'Is it time to Quit 'Quiet Time'?'. They suggest that reliance on the common evangelical practice of the Quiet Time (which, as the article notes, emerged in US evangelicalism in the late 19th century) needs to be reformed, with a greater emphasis placed on communal reading and longer passages of Scripture:

When my freshmen described their daily quiet times, I began to understand some of the disconnect. They lacked extended communal readings of Scripture where it was safe to interrogate the text and puzzle over its meaning ... If today’s common rituals of Bible engagement are not working, then we must disrupt them in favor of deep learning practices. These new habits could consist of communal listening, deep diving, repeated reading of whole books of the Bible, or some other strategy. But the assumption that daily devotions alone will yield scriptural literacy and fluency no longer appears tenable, because it never was ... we may need to shift the devotional center of gravity away from solitary practices and toward communal ones.

Mattins and Evensong, of course, were designed to provide such communal reading of scripture. As Cranmer stated:

that the people (by daily hearing of holy Scripture read in the Church) might continually profit more and more in the knowledge of God, and be the more inflamed with the love of his true Religion.

What is more, rather than the short passage traditionally associated with the Quiet Time, the traditional Prayer Book lectionaries for Mattins and Evensong follow Cranmer's intention that "all the whole Bible (or the greatest part thereof) should be read over once every year". As Eamon Duffy notes in his praise for Choral Evensong - "the greatest liturgical achievement of the Reformation" - it has "at its heart ... the reading of two extended passages of Scripture, one each from the Old and New Testaments".

And it is this - the two substantial readings from scripture, reading the Bible over the course of the year - that also encourages the 'puzzling over the meaning' called for by Johnson and Durgin. The juxtaposition of Old and New Testament readings can sometimes be disconcerting; odd, weird, and distasteful passages of scripture are not (usually) omitted; contrasts and contradictions are confronted.

This approach to the reading of scripture - substantial passages, Old and New Testament readings, following a canonical pattern of reading - contributes to that "deep diving" which the article urges. It also embodies how scripture changes us: slowly, over time, as we read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest.

There is also a significant communal aspect even while praying Mattins or Evensong alone. Others are sharing these offices with me as they too pray them. We are reading scripture in the same context of confession, praise, and prayer. And, while apart, we are together reading scripture and seeking therein to discern how it proclaims, points to, and contemplates the purposes of God.

Comments

Post a Comment