Ending 'the late unhappy confusions': St. Bartholomew's Day 1662 and episcopal orders

Provided alwaies and be it enacted that from and after the Feast of St. Bartholomew which shall be in the yeare of our Lord One thousand six hundred sixty and two no person who now is Incumbent and in possession of any Parsonage Vicarage or Benefice and who is not already in Holy Orders by Episcopall Ordination or shall not before the said Feast day of St. Bartholomew be ordained Preist or Deacon according to the forme of Episcopall Ordination shall have hold or enjoye the said Parsonage Vicaradge Benefice with Cure or other Ecclesiasticall Promotion within this Kingdome ... but shall be utterly disabled and (ipso facto) deprived of the same.

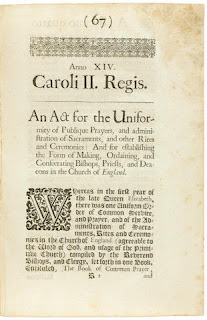

The requirement of the 1662 Act of Uniformity that those holding office in the Church of England, but who had not been ordained by a bishop, must receive episcopal orders, was one of the Act's most controversial provisions. Non-conformist critics declared that it enshrined a un-reformed view of episcopacy, alien to the post-Reformation Church of England before Laud. They also darkly muttered that it unchurched the non-episcopal Reformed Churches on the continent.

It is rather ironic that more than a few contemporary Anglican commentators utter similar condemnation of this provision of the Act of Uniformity. There was nothing at all innovative about the provision. Since the publication of the first reformed English ordinal in 1550, the requirement of episcopal ordination had been explicitly stated:

And therfore to the entent these orders shoulde bee continued, and reverentlye used, and estemed in this Church of England, it is requysite, that no man (not beynge at thys presente Bisshop, Priest, nor Deacon) shall execute anye of them, excepte he be called, tryed, examined, and admitted, accordynge to the forme hereafter folowinge.

Occasionally it was the case that individuals who had received non-episcopal orders in continental Reformed Churches were granted office in the Church of England: these were the very rare exceptions which proved the rule. The Church of England was an episcopally ordered church, its ministers receiving episcopal orders, "to the entent these orders shoulde bee continued".

The anti-episcopal agitation in the Elizabethan, Jacobean, and Caroline Church was consistently confronted by defenders of the Elizabethan Settlement: Hooker, "if any thing in the Churches Government, surely the first institution of Bishops was from Heaven, was even of God, the Holy Ghost was the Author of it" LEP VII.5.10; Bancroft, "you must know that the church of God ever since the apostles times, hath distributed the ecclesiasticall ministerie principallie into these three parts, Bishops, Priests, and Deacons"; Downame, "the episcopall function, or gouernment by bishops, is of apostolicall institution: therefore the episcopal function is a divine ordinance". Contrary to how Non-conformist critics used the phrase, it was the theology of such "old Episcopal divines" which underpinned the 1662 Act of Uniformity requiring episcopal orders: to refuse episcopal orders, was to reject an apostolic ordering of the Church.

After decades of anti-episcopal agitation came the deluge of the 1640s and 50s. The office, title, and authority of bishops was abolished by Parliament in 1646. In the place of the episcopal regiment, Parliament adapted the proposals of the Westminster Assembly, producing a form of government condemned by the Scots - in a rather catchy phrase - as "lame erastian presbytery". Morrill's account of this system is rather damning:

The reorganisation never really got off the ground. Although it gained majority support in the Houses, there was no general support for it in the country ... Without central backing ... the whole rationale failed. Although the ordinances enjoining the Presbyterian order remained in force from 1645 to 1654, they became increasingly inoperative ... Only in two areas (London and Lancashire) does the provincial machinery ever seem to have come into being.

It was, in other words, an utterly dysfunctional form of church government. As one of the Westminster divines, Daniel Cawdry, admitted in 1652, "our churches yet stand, for the most part, unpresbytered, and without a settled government". Amidst such dysfunction, Cromwell introduced a pragmatic attempt to provide ecclesiastical order when, in 1654, he created the Commissioners for the Approbation of Public Preachers, known as the Triers. Crucially, however, as Taylor and Fincham note in their excellent study of the illegal episcopal ordinations during 1645-1660, this system had no reference to ordination:

Applicants had to submit testimonials from at least 'three persons of known godliness and integrity', but not their letters of orders, for ordination was outside the commission’s purview and some were admitted without being ordained.

Such was the ordering of the Churches of England and Ireland during "the late unhappy confusions". Some ministers were ordained by a Presbyterian system, some by the congregational system of Independency, some were not ordained in any way. Alongside this, as Taylor and Fincham have demonstrated, "a remarkably large number of men received episcopal ordination between 1646 and 1660", around 2,500:

The consequence was that numerous illegally episcopally-ordained ministers, sometimes presented to livings by first Oliver and then Richard Cromwell, were approved by the Triers

In other words, after the dysfunction of the system put in place by Parliament in the mid-1640s, Cromwell's Triers then presided over ecclesiastical confusion, with no common ordering of ministers. This was the state of affairs inherited by the Church of England at the Restoration. It was, therefore, a wise, prudent, and modest measure of the 1662 Act of Uniformity to restore the common order of the Church of England, ensuring that all clergy had recognised, common, shared orders.

The notion that this unchurched the non-episcopal Reformed Churches of the Continent was fanciful. Taylor and Fincham point to the anti-Laudian Morton and the Laudian Duppa, two of the bishops who continued to ordain during the Interregnum. Both bishops, despite their theological differences, agreed that no comparison could be made between England in 1645-60 and the necessity which had led some continental Reformed Churches to possess a non-episcopal order:

Bishops Morton and Duppa ... denied that it could: episcopacy had been wilfully overthrown, bishops were still available to give orders, and it followed that English presbyters were not lawfully ordained and their church schismatical.

Morton's stance also demonstrates that the Act of Uniformity requiring episcopal was no high-flying Laudian innovation. Indeed, Calvinist and moderate non-Laudian bishops were amongst the most active in bestowing orders during these years. Requiring episcopal ordination, rather than a Laudian innovation, was an expression of consensus and moderation, a practice and conviction shared by Calvinist, moderate, and Laudian bishops.

The Act of Uniformity was also accompanied by a return to the Hookerian understanding of episcopacy as apostolic and divine ordinance. Sancroft's sermon at the December 1660 consecration of seven bishops for the Church of England was an example of this:

I cannot see, why we may not with some Confidence infer the Apostolical, and, at least, in Consequence thereupon, the Divine Right of our Ecclesiastical Hierarchie, how harsh soever it sounds, either at Rome, or Geneva.

Against the de jure claims of Rome and Geneva, the reformed Church of England was again claiming that the episcopal order was divinely instituted. Sancroft took care - following the example of Elizabethan, Jacobean, and Caroline divines (including, by the way, Laud) - to distinguish between the episcopal office being of divine right, and its exercise relying on the Royal Supremacy, "onely by, and under the Permission of Pious Kings".

As with Hooker, Sancroft gave expression to an understanding of episcopacy in which claims to divine institution were secondary to, "in Consequence thereupon", to its apostolic nature. The apostolicity of episcopacy had, of course, been declared in the Preface to the Ordinal since 1550. The Act of Uniformity required nothing beyond this and assent to the practice of episcopal ordination. Simon Patrick's 1662 pamphlet A brief account of the new sect of latitude-men, said of this grouping, "they do very sincerly esteem Episcopal government, both as in it self the best, and of Apostolical antiquity". Put bluntly, this was sufficient for conformity and ordination. To reject this was to explicitly reject the good order and peace of the Elizabethan Settlement. As the moderate Calvinist John Gauden, Bishop of Worcester, asked in his 1662 visitation articles:

Is your Minister Episcopally Ordained (Deacon or Priest) according to the Laws of the Realm of England, and the ancient practice of the Church universall, no lesse then of this National Church?

Such was the nature of the restoration of episcopal order to the Church of England after "the late unhappy confusions". Restoring a common order to the ministry of Word and Sacrament, the Act of Uniformity healed the deep wounds inflicted by the confused, failed church order of the 1640s and 50s. Crucially, it did not - contrary to the allegations of the Non-conformists - unchurch the continental non-episcopal Reformed Churches: the Church of England's relationships with those Churches throughout the 'long 18th century' were positive, supportive, and respectful. The concern of the Act of Uniformity in requiring episcopal ordination was to restore order to the Churches of England and Ireland.

As for the ministry of those who had not received episcopal orders during "the late unhappy confusions", the Act required no condemnation or rejection of this. Perhaps no better summary of the wise, peaceable, modest intention of Saint Bartholomew's Day 1662 is to be found than in the Letters of Orders given by Bramhall, the Laudian Archbishop of Armagh, to those non-episcopally ordained ministers in his diocese on whom he bestowed episcopal orders:

that he did not annual the minister's former orders, if he had any, nor determine their validity or invalidity: much less did he condemn all the sacred orders of foreign churches, whom he left to their own judge; but he only supplied, whatever was before wanting, as required by the Canons of the Anglican Church [in the original, Ecclesiae Anglicanae]; and that he provided for the peace of the Church, that occasions of schism might be removed, and the consciences of the faithful satisfied, and that they might have no manner of doubt of his ordination, nor decline his presbyterial acts as being invalid.*

(*Found in Bolton's The Caroline Tradition in the Church of Ireland.)

Comments

Post a Comment