Good Lord, deliver us: praying the Litany in the face of evil

Many of us will, quite naturally, have found praying for such dark, tragic circumstances very difficult. I certainly found it futile to rely on my own resources, my own thoughts, my own words.

What was I to pray for?

What could be said?

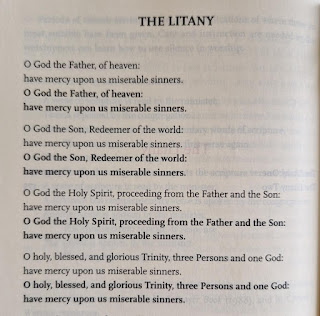

On Sunday, Wednesday, and Friday, however, the Litany was said.

And it was in the Litany, once again, that I found the words that gave meaning and shape to my attempts to pray for a dark, tragic situation.

From all evil and mischief ... from the craft and assaults of the devil; from thy wrath, and from everlasting damnation, Good Lord, deliver us.

Evil. Devil. Wrath. Damnation. Yes, those words were necessary. As a friend commented on Twitter, in response to a rather weak statement urging the Church to say of the murderer that no-one is beyond God's grace:

Nobody is beyond the love of God, but evil is a reality and we have the freedom to act on it if we wish - causing grave danger to our own souls ... Underlying much Christian universalism of the last ~150 years is often unvoiced faith in secular technocracy: crime is a result of social problems/bad parenting, will [therefore] be remedied eventually & criminals are effectively victims of circumstance. That theory breaks down here.

In the face of stark evil, a weak theology that seems incapable of using the words evil, devil, wrath, and damnation is exposed. This also has significance for liturgy. The contemporary version of the Litany in the Church of Ireland BCP 2004 has no equivalent to the above petition: the "snares of the devil" are mentioned, but there is no reference to evil, wrath, damnation. 'Evil' does appear in the Common Worship version of the Litany, but wrath and damnation have disappeared. It is the Great Litany in TEC's BCP 1979 which has wisely retained much of the 1662 petition, although here too 'thy wrath' unfortunately is absent:

From all evil and wickedness; from sin; from the crafts and assaults of the devil; and from everlasting damnation, Good Lord, deliver us.

It is another example of cruel, dark times needing the robust theological vision of traditional Prayer Book liturgy, unafraid to state that evil and the devil profoundly distort our humanity; that to embrace evil and its empty darkness is to radically turn away from the God of light, life, and love; that wrath and damnation are words which rightly describe the consequences of such a radical turning away from God.

From battle and murder ... Good Lord, deliver us.

The evil of murder was set before our eyes during the reporting of the trial. In a culture which is losing a moral discourse which adequately and convincingly communicates the dignity of human life, to pray for deliverance from murder is to restate that dignity and our duties towards one another. In the words of the 1662 Catechism:

To hurt no body by word or deed ... To bear no malice nor hatred in my heart.

We might also think of the older Anglican practice of reciting the Commandments at the Holy Communion and Ante-Communion, regularly setting before us God's solemn call to recognise the dignity of life:

Thou shalt do no murder.

And so we pray in the Litany:

That is may please thee to give us an heart ... diligently to live after thy commandments; We beseech thee to hear us, Good Lord.

Most shocking in this case was that the victims were newly born infants in hospital.

That is may please thee to preserve ... all women labouring of child ... and young children ... Good Lord, deliver us.

This petition in the Litany reflects, of course, an age when deaths in infancy - and deaths of women in childbirth - were common. As such, we might doubt its contemporary relevance. This, however, ignores the experience of too many woman and infants across the globe, for whom these grim realities continue. What is more, it also ignores the reality of the inherent vulnerability of infants and young children in all societies, and the natural fear and anxiety that most women have in as child birth approaches.

To not include such petitions in the Litany is to foolishly think our society is somehow liberated from these fears and vulnerabilities. The same hubris excluded petitions for deliverance from plague and pestilence from contemporary litanies.

It has been sobering in recent days to reflect that the same petition which includes "all women labouring of child ... and young children", also prays this:

That is may please thee ... to shew thy pity upon all prisoners and captives.

This is a petition that I usually value, thinking of those who I know who work with prisoners. In the days following the trial and conviction, however, I have found this petition deeply uncomfortable. In it, I pray for a convicted serial killer of little children. My discomfort, of course, is part of the reality of Christian prayer. The Litany, after all, only a few petitions later, prays "forgive our enemies [and] persecutors": a prayer for those in Putin regime directing the invasion of Ukraine, a prayer for those Islamist militants persecuting Christians in Nigeria and Pakistan.

The same critique of a theology and liturgy that seems incapable of using the words evil, devil, wrath, and damnation also applies to a theology and liturgy incapable of of taking seriously the call of Jesus that we be "the children of your Father which is in heaven": holding in prayer before the God who is life and light, righteousness and truth those who are our enemies and persecutors, and those who have murdered the innocent.

Such prayer, however, is no cheap grace. In the confession at Holy Communion, we say of our routine sins:

The remembrance of them is grievous unto us; The burden of them is intolerable.

I am not sure I can imagine the searing, blinding pain that would consume a murderer of little children, when acknowledging their sins before the God who is life and light, righteousness and truth.

That is may please thee to have mercy upon all men; We beseech thee to hear us, good Lord.

The mercy of God cleanses the wounds of our sin, but such cleansing stings deeply, our wounds exposed, the poisoned roots painfully removed.

Such prayers are not cheap grace.

The Litany ends with a stark reminder that in praying for sinners we are praying for ourselves:

That it may please thee to give us true repentance ... Good Lord, deliver us.

The Litany, yes, has given me a means to pray for those who have known unimaginable pain and loss at the hands of another.

The Litany has given me a means to pray that our society would be delivered from dark evil.

The Litany has also given me a means of holding before God those who commit great evils; no cheap grace because the searching, cleansing light of God, "pierc[es] even to the dividing asunder of soul and spirit, and of the joints and marrow, and is a discerner of the thoughts and intents of the heart". The shame of acknowledging our routine sins can be bitterly painful. What, then, of the bitter pain of confessing the murder of little innocents?

But the Litany ends by calling me to repentance. I have wounded others and denied their dignity. I have failed to love my neighbour. I have borne hatred and malice towards others. The Litany ends by bringing me before the God who is life and light, righteousness and truth, where my sins are exposed.

Forgive us all our sins, negligences, and ignorances.

Thank you for this beautiful reminder. How often should I pray the litany privately and when?

ReplyDeleteThank you for your kind words.

DeleteAs to praying the Litany privately, I think it is a wholesome practice for clergy to do so as per the rubric (Sunday, Wednesday, Friday). For lay people who may wish to pray to the Litany, I certainly would not set any hard and fast rule. Perhaps once a week might be a good practice, providing a means and focus of weekly intercession. Prayed slowly, it can be said in 10 minutes, so it is not onerous. This being so, any time and place which allows this would be appropriate.