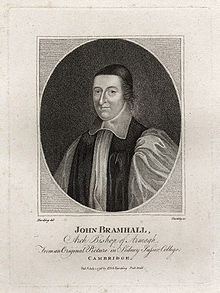

'Maintaining a communion both with the Western and Eastern Churches': Bramhall and Laudianism 's catholic vision

I deny, that the Protestant Bishops did "revolt from the Catholic Church". Nay, they are more Catholic Bishops in that, than the Roman Catholics themselves; maintaining a communion, for the foundations and principles of Christian religion, both with the Western and Eastern Churches, whom the Church of Rome excommunicates from the society of the mystical Body of Christ, limiting the Church to Rome and such places as depend upon it, as the Donatists did of old to Africa. It is true, the Protestants separated themselves from the communion of the Roman Church; yet not absolutely, nor in such fundamentals and other truths as she retains, but respectively, in her errors, superstructions, and innovations. And they left it with the same mind, that one would leave his father's or his brother's house, when it is infected with the plague: with prayers for their recovery, and with desire to return again, so soon as it is free, and that may be done with safety (Protestants' Ordinations Defended, IV.2).

Bramhall's response reflects how Laudianism cohered with an earlier Conformist understanding of the Church of Rome as a church in error rather than as the anti-Christ. This also, as seen in the declaration of James VI/I, provided an opening for the hope of the restoration of the unity of the Western Church through, on the one hand, a process of reform in the Roman Church (with somes hopes that this was seen in Gallicanism and Jansenism) and, on the other, a recognition of the See of Rome as patriarch of the West. As such, we might identify this as an antecedent for later ecumenical encounters between Anglicanism and Roman Catholicism, beginning with the Malines Conversations and intensifying after the Second Vatican Council. In particular, Bramhall's insistence that the separation of the ecclesia Anglicana from the Roman Church was "not absolutely, nor in such fundamental and other truths as she retains" has an echo in what Archbishop Michael Ramsey and Pope Paul VI described in their 1966 Declaration as "the ancient common traditions".

No less significant for the Laudian catholic vision which Bramhall articulates, is his statement of the episcopate of the ecclesia Anglicana sharing in the apostolic faith professed by West and East: a vision, we might say, of the Church breathing with 'both lungs'. This 'looking East' has been a significant part of Anglican self-understanding, consistently pointing to the Churches of the East - in their profession of patristic orthodoxy, their life as episcopal, national churches rejecting papal jurisdiction, with married clergy and communion in both kinds, and not accepting Roman dogmatic definitions - as demonstrating that the non-papal, patristic Catholicism of the reformed ecclesia Anglicana (and of the other episcopal, liturgical, sacramental Churches of the Northern Kingdoms) was no innovation.

Bramhall, in other words, powerfully reminds us that Laudianism was not English ecclesial nationalism, opposed to internationalist Puritan and Papalist alternatives. No, Laudianism evoked a rich vision of the Church Catholic in an age of division: separated from Rome yet sharing with it, in the words of Hooker, "that which is ancienter and better"; and confessing with the East the non-papal Catholic faith of the patristic churches.

Comments

Post a Comment