Cosin, Brevint, and Durel: understanding episcopal ordination amidst French Reformed order

I never refused to join with the Protestants, either here or anywhere else, in all things wherein they join with the Church of England. Many of them have been here at our Church and we have been at theirs. I have buried divers of our people at Charenton, and they permit us to make use of their peculiar and decent cemetery here in Paris for that purpose; which if they did not, we should be forced to bury our dead in a ditch. I have baptized many of their children at the request of their own ministers, with whom I have good acquaintance, and find them to be very deserving and learned men, great lovers and honourers of our Church ... Many of their people, (and of the best sort and quality among them,) have frequented our public prayers with great reverence, and I have delivered the Holy Communion to them according to our own order, which they observed religiously. I have married divers persons of good condition among them. I have presented some of their scholars to be ordained Deacons and Priests here by our own Bishops (whereof Monsieur de Turenne's Chaplain [Brevint] is one, and the Duke de la Force's Chaplain [Durel] another), and the Church at Charenton approved of it : and I preached here publicly at their ordination. Besides, I have been (as often as I had spare time from attending our own congregation) to pray and sing psalms with them, and to hear both the weekly and the Sunday sermons, at Charenton.

This passage came to mind following the recent post on the 1756 German Church in Halifax, Nova Scotia. As discussed in that post, the circumstances surrounding the episcopal ordination of the Lutheran pastor of the German congregation do not at all suggest a renunciation of Lutheran orders. The congregation were supportive of his episcopal ordination and a Lutheran congregation in London - where he received episcopal orders - invited him to preach during his stay: this, of course, would have been unlikely if it was understood that he was denying his Lutheran orders.

Something rather similar seems to have happened in the events of over a century earlier, as described by Cosin. There is no indication that the two French Reformed ministers - Brevint and Durel - who he presented for episcopal ordination (at the hands of Thomas Sydserf, the exiled Bishop of Galloway) were renouncing their French Reformed orders. As with the German congregation of Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1785, Cosin points to the approval of the well-known French Reformed congregation with which he was associated:

and the Church at Charenton approved of it.

Significantly, after receiving episcopal orders on Trinity Sunday, 1651, Brevint and Durel continued to minister in French Reformed circles. As Cosin notes, Brevint served as chaplain to the Duke de la Force and Durel as chaplain to the Viscount of Turenne. Both these leading families had great prominence in French Reformed circles. It is difficult to imagine how such positions would have been possible for Brevint and Durel if their episcopal ordination was regarded as a rejection of French Reformed orders.

In addition to this, there is Cosin's ongoing relationship with the Reformed congregation in Charenton. Again, it is difficult to imagine how this would have continued, with obvious warmth and respect on both sides, if Cosin was viewed as being instrumental in rejecting French Reformed orders.

Finally, there is Durel's 1662 work, A view of the government and publick worship of God in the reformed churches beyond the seas, a defence of the 1662 Settlement. In it Durel declares that the French Reformed are "no enemies to Episcopal Government", and speaks in a thoroughly Hookerian fashion of their then existing order:

The French Churches I am certain are so far from any averseness to it, that they rather wish they were in a condition to enjoy that sacred Order, and to reap the benefit that may come to the Church of God through the same; all understanding men amongst them saying plainly, That if God Almighty were pleased that all France should embrace the Reformed Religion, as England hath, the Episcopal Government must of necessity be established in their Churches; as now the equality of their Ministers, is for many reasons found the fittest in the low condition they are in at present.

Quite clearly, this does not at all read as a rejection of French Reformed orders. In fact, as suggested above, there seems to be an obvious echo of Hooker in accepting that current order.

This, of course, leaves us wondering as to why Brevint and Durel, as Cosin's urging, received episcopal orders. Both Brevint and Durel were subjects of the English Crown, having been born on Jersey: this in and of itself would have been grounds for urging them to receive episcopal orders. Cosin describes them as "scholars", suggestive of their abilities as theologians, abilities which could be - and were - put to use in defence of the cause of the Church of England. If they were to serve in the Church of England - whether in exile or after a much hoped-for restoration - episcopal orders were necessary. Both Brevint and Durel went on, of course, to hold posts in the Restoration Church of England: Brevint as Dean of Lincoln and Durel as a royal chaplain and canon of St. George's, Windsor.

As with the case of the Lutheran pastor of the German congregation in Halifax Nova Scotia, becoming a SPG missionary a century-and-a-half later, ministerial office in the Church of England required episcopal ordination for the sake of the Church's good order. And the necessity for good order was painfully obvious in the 1650s, amidst ecclesiastical disorder and anarchy in England.

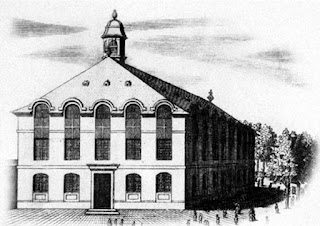

In other words, we have here two examples - from 1651 and 1785 - of non-episcopally ordained ministers receiving episcopal orders from the Church of England in a manner which does not at all suggest a renunciation of non-episcopal orders. In both cases, the good order of the Church of England, rather than a negative judgement about continental Protestant non-episcopal orders, appears to be the motivation for the giving and receiving of episcopal orders.(The first illustration is of the French Reformed church at Charenton, attended by Cosin during his Paris exile. At the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, the church was destroyed by the French authorities. The second is of the memorial to Daniel Brevint in Lincoln Cathedral, where he was Dean 1682-95.)

Comments

Post a Comment