'The flames of a consuming Civil War': an 18th century Anglican defence of imagery on the iconclasm of the 1640s

the Flames of a consuming Civil War burst out with irresistible Violence, and spread an universal Chaos of Confusion. In the preceding Tumults indeed, Lord Clarendon relates, that seditious and factious Persons caused the Windows to be broken down in Churches, and committed in them many other insolent and scandalous Disorders.

However, after the military Standard was erected, these profane Outrages were greatly increased. Some stately religious Fabrics were totally demolished; many were converted into Stables, or polluted and profaned by other shocking Abominations. Their beautiful Sculptures, though only containing Scripture Histories, were absurdly broken down with Axes and Hammers, their Monuments, erected to illustrious and venerable Personages, were defaced; the very Urns, in which their Ashes had been deposited, were ransacked; and their consecrated Utensils were exposed to Rapine and Plunder. Crosses, whether graved or delineated, whether in Churches or out of them, were peculiar Objects of an Enthusiastic Aversion. Nor less was their Rage levelled against painted Glass, containing in it either Portraitures of Prelates and Kings, of Fathers and Martyrs, of our Saviour and his Apostles or Representations of Scripture Histories.

The pious captive Sovereign, amidst all his Calamities, could not forbear taking Notice of this 'breaking of Church Windows'; this 'pulling down of Crosses; this defacing of the Monuments and Inscriptions of the Dead, &c. as the malignant Effects of popular, specious, and deceitful Reformations'.

The final paragraph of this extract quotes from Eikon Basilike, placing Parliamentarian iconoclasm in the context of a wider theological and ecclesiastical agenda, tearing down the Elizabethan Settlement, including the imagery retained:

The specious and popular titles, of Christs Government, Throne, Scepter, and Kingdome, (which certainly is not divided, nor hath two faces, as their parties now have, at least) also the noise of a through Reformation, these may as easily be fined on new models, as fair colours may be put to ill-favoured figures.

The breaking of Church-windowes, which Time had sufficiently defaced; pulling down of Crosses, which were but civill, not Religious marks; defacing of the Monuments, and Inscriptions of the Dead, which served but to put Posterity in mind, to thank God, for that clearer light, wherein they live; The leaving of all Ministers to their liberties, and private abilities, in the Publick service of God, where no Christian can tell to what he may say Amen; nor what adventure he may make, of seeming, at least, to consent to the Errours, Blasphemies, and ridiculous Undecencies, which bold and ignorant men list to vent in their Prayers, Preaching, and other Offices. The setting forth also of old Catechismes, and Confessions of Faith new drest, importing as much, as if there had been no sound or clear Doctrine of Faith in this Church, before some four or five yeares consultation had matured their thoughts, touching their first Principles of Religion.

All these, and the like are the effects of popular, specious, and deceitfull Reformations, (that they might not seem to have nothing to do) and may give some short flashes of content to the vulgar, (who are taken with novelties, as children with babies, very much, but not very long) But all this amounts not to, nor can in Justice merit the glory of the Churches thorow Reformation; since they leave all things more deformed, disorderly, and discontented, then when they began, in point of Piety, Morality, Charity, and good Order.

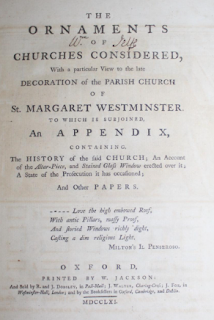

The account given in The Ornaments of Churches Considered, echoing Eikon Basilike, emphasises how the iconoclasm of the 1640s points to the retention of imagery by the Elizabethan Settlement. Put simply, the widespread and destructive iconoclasm would not have occurred had it not been for such retention. Any church improvements in the Caroline period could not have been so widespread as to require the extended and organised violence of the official iconoclasm of the 1640s. This is particularly evidenced by William Dowsing's Journal, recording his activities as, on the authority of Parliament, he inflicted iconoclasm on the churches of Cambridgeshire and Suffolk in 1643 and 1644. As his entries demonstrate, many of the targets of his destructive fury clearly pre-dated the reign of Charles I, and were present in an abundance of quite ordinary parish churches.

Comments

Post a Comment