'Thus shall we declare that Christ's gifts and graces have their effect in us': the Old High heart at Holy Week and Easter

We begin with the excellent Episcopalian Reformed theologian Fleming Rutledge on Good Friday:

It is a minority POV these days, but for me today, a noonday service with powerful sermon and the "old" Prayer Book service with all the readings and prayers but no communion and no "veneration of the cross" seemed perfect to me.

— Fleming Rutledge (@flemingrut) March 29, 2024

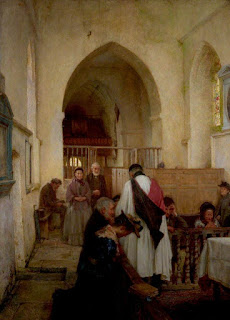

Good Friday is surely a day for such a stark, unfussy liturgy, not overwhelming the senses, a liturgy which stills us in heart, mind, and soul before the mystery of the Cross, proclaimed by prophets, apostles, and evangelists. Too much movement, receiving the Sacrament only hours after reception on Maundy Thursday, overwhelming (and, simultaneously, necessarily inadequate imagery): this can - for some of us - distract rather than aid, failing to still us before the word of the Cross.

For an example of a Prayer Book Good Friday we can turn to St. Giles-in-the-Fields, London:

Mattins and the Litany this morning. pic.twitter.com/bwZvJlJQvJ

— Tom Sander 🚴 (@RevThomasSander) March 29, 2024

One person, who had attended the service, commented on 'X' that it was "the most moving service of Mattins I have ever experience". Such can be the effect of a sober, restrained service of Matins on Good Friday, setting before us the Crucified One who seeks not a kiss of the lips but the faithful obedience of heart and soul.

Then there is Easter Eve:

Confession time

— Fr. David (@PBCatholic) April 1, 2024

I didn't go to an Easter Vigil this year for the first time in as long as I can remember.... and I didn't miss it. Don't get me wrong. I'm glad the 79 BCP introduced it but I've come to an appreciation of the quiet restrained Easter Even of historic Anglicanism

I have previously sought to articulate something of this. It is not to argue against those who value the Vigil and celebrate it in a packed church. It is, rather, to say that those of us who value an Easter Eve marked by Matins, Ante-Communion, and Evensong - and thus no Vigil - are not opting for a somehow inferior commemoration of the day. It is a pattern which both allows for reflection on the Lord's descent to the dead and prepares us for the celebration of Easter Day.

Easter is a time to again be grateful for the churchyard, as Fergus Butler-Gallie wonderfully explored:

The power of Easter is that it doesn’t deny the pain or darkness of death, but places it in the context of eternal hope.

— Engelsberg Ideas (@EngelsbergIdeas) March 31, 2024

An Easter elegy | @_F_B_G_ https://t.co/QpPYegDYmQ

The headstones and memorials in the churchyard - with their tributes and memories - are not to be dismissed as the stuff of 'natural religion' (as if natural religion were a bad thing). No, they point to the reality of death gathered up and transformed in the hope of Easter:

The power of Easter is that it absolutely – necessarily, even – embraces the reality of death, yet also refuses to grant it dominance. It doesn’t pretend that those who lie in the dark of the earth by the Padburys or the little Edens or Mr Whippy are not dead, but nor does it define them by that fact. It doesn’t deny the pain or darkness of death, but it places it in the context of hope.

Then there was Easter Monday in Halifax, Nova Scotia:

Commemorated Monday in Easter Week in a freezing cold unheated chapel with a 1662 BCP North-end celebration of Holy Communion, with the reading of the Homily "Of the Resurrection for Easter day" from the 2nd Book of Homilies.

— Nicholas ⚓ (@nic_lucc) April 1, 2024

P.s. most of the congregations was in their 20-30s. pic.twitter.com/xXxbQIynzg

No doubt regarded as terribly 'low church' by some contemporary Anglican opinion, this was - of course - a deeply Laudian and Old High celebration: the priest duly vested in surplice and tippet, north end signifying the relationship between the commemorative sacrifice of the Eucharist and the intercession of our Great High Priest, the communicants humbly kneeling to receive, on Monday in Easter Week as provided for in the decent rite of the Prayer Book, with Cranmer's grand proper preface for Easter Day "and seven days after". And as for the Book of Homilies, it was Laudian bishops who upheld it in the face of Puritan attacks.

The Homily for Easter Day has a quite beautiful conclusion:

Let us Christian folk keep our holy day in spiritual manner, that is, in abstaining, not from material leavened bread, but from the old leaven of sin, the leaven of maliciousness and wickedness. Let us cast from us the leaven of corrupt doctrine, that will infect our souls. Let us keep our feast the whole term of our life, with eating the bread of pureness of godly life, and truth of Christ's doctrine. Thus shall we declare that Christ's gifts and graces have their effect in us, and that we have the right belief and knowledge of his holy resurrection: where truly if we apply our faith to the virtue thereof in our life, and conform us to the example and signification meant thereby, we shall be sure to rise hereafter to everlasting glory, by the goodness and mercy of our Lord Jesus Christ, to whom with the Father and the holy Ghost be all glory, thanksgiving, and praise, in infinita seculorum secula, Amen.

It is a paragraph in which gives voice to a number of characteristics found in Old High, Prayer Book piety. The truth of the Easter proclamation is not found in ceremonies but in Word and Sacrament. The Easter faith takes root within us not in mystical experiences but in holy living amidst the ordinary duties and callings of daily life: "thus shall we declare that Christ's gifts and graces have their effect in us". And it bears fruit in the quiet hope of the life everlasting, sustaining us over "the whole term of our life".

Holy Week and Easter are not to be a dramatic re-enactment of the unique and unrepeatable events of Cross and Resurrection; they are yearly observances which call us in heart, mind, and soul to be renewed by Word and Sacrament in communion with the One who is the first-fruits of the Resurrection. A multiplicity of ceremonies and images and actions can, for some of us, be overpowering and distracting: much better (again, for some of us) the sober, restrained approach of the Prayer Book, allowing us to focus in heart, mind, and soul on the Cross and Resurrection proclaimed in Word and Sacrament. We might hope that the current suggested in this post will continue to flow, not least in a cultural context bombarded by imagery, constant distraction, and a chasing after experiences.

Finally, one of my own posts from Easter Monday, suggestive - I hope - of the modest, decent, noble simplicity of Old High piety at Holy Week and Easter:

Again this year on Easter Monday, I stop at the lychgate at The Middle Church, in the heart of Jeremy Taylor country, to admire its quiet but confident proclamation of the Easter faith. pic.twitter.com/AjdjNIrXX7

— laudablePractice (@cath_cov) April 1, 2024

Comments

Post a Comment