"And seek afresh our absolution": how the Ordinariate daily office sides with the Puritans

This was a point of contention in the fierce debates between Conformists and Puritans in the Elizabethan and Jacobean Church. In the 1603 Millenary Petition, Puritans insisted that amongst the "divers terms" which should be removed from the Prayer Book was 'absolution'. At the Hampton Court conference, the Puritans renewed their demand for the removal of the term, "Because Absolution implyeth forgiving of sins with authority".

James I, of course, rejected the Puritan demand, instead permitting only the addition of the word "Remission". Such addition did not alter the understanding that this was indeed an Absolution. Sparrow explicitly relates it to John 20:23, going on to state:

Which power of remitting sins was not to end with the Apostles, but is a part of the Ministry of Reconciliation, as necessary now as it was then, and therefore to continue as long as the Ministrry of Reconciliation, that is, to the end of the world. When therefore the Priest absolves, God absolves, if we be truly penitent.

Comber similarly declares:

this unloosing men from the bond of their sin is that, which we properly call "absolution", and it is a necessary and most comfortable part of the priest's office.

This understanding was a commonplace of conventional High Church teaching throughout the 18th and well into the 19th century, as the 1874 pastoral letter from Christopher Wordsworth, Bishop of Lincoln, classically demonstrated.

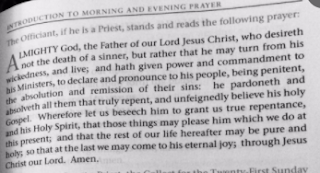

The Ordinariate office book, however, is a rejection of this Caroline and High Church teaching, siding with the Puritans: it removes (as seen in the picture above) the term 'Absolution' from this act by the priest.

What is more, it is not only a case of the Ordinariate here siding with the Puritans and rejecting Caroline and Old High teaching. It is also a rejection of the Tractarians. Keble had celebrated the efficacy of the Absolution at Mattins and Evensong in his 'The Three Absolutions', in which the Absolution in the daily service was set alongside that in the Holy Communion and the Visitation of the Sick, all three being an exercise of the power of keys:

Each morn and eve, the Golden Keys

Are lifted in the sacred hand,

To shew the sinner on his knees

Where Heaven's bright doors wide open stand.

Newman likewise pointed to the efficacy of the Absolution in the daily office. In a passage from one of the Parochial and Plain Sermons, Newman beautifully evoked the experience of the grace of Absolution in the daily offices:

Let us but consider how we have fallen from the light and grace of our Baptism. Were we now what that Holy Sacrament made us, we might ever ''go on our way rejoicing;" but having sullied our heavenly garments, in one way or other, in a greater or less degree (God knoweth! and our own consciences too in a measure), alas! the Spirit of adoption has in part receded from us, and the sense of guilt, remorse, sorrow, and penitence must take His place. We must renew our confession, and seek afresh our absolution day by day, before we dare call upon God as "our Father," or offer up Psalms and Intercessions to Him.

Divine Worship: Daily Office does, of course, have its reasons for this significant revision, here conforming the Prayer Book offices to the norms of Roman theology and the understanding of absolution being reserved to the Sacrament of Reconciliation. This, however, loses a distinct and significant aspect of how Mattins and Evensong were (and can continue to be) a "principle means of grace for Anglican Christians". Ironically siding with the Puritans, and rejecting the rich teaching of the Old High and Tractarian traditions, the inability of Divine Worship: Daily Office to recognise the gift of Absolution at Mattins and Evensong represents a profound break with classical Anglican piety and theology.

I for one as an Ordinariate member was delighted to see the re-appearance of the text of the Absolution for Morning & Evening Prayer - it certainly wasn't in the Customary of OLW (a hastily produced precursor of this book for the Ordinariate). You might see a moving away from Anglican theology in the change in rubrics, but then the rubrics are not reproduced from the prayer book throughout: I see a direction of travel in its inclusion that is welcome, at the very least an unwillingness to exclude the text even if it isn't patent of a strictly Roman interpretation.

ReplyDeleteTimothy, many thanks for your comment. Yes, it is good to see the text of the Absolution in the Divine Worship: Daily Office. But, the 1662 rubric has profound theological significance. The use of the term 'Absolution' has a meaning that is not - and cannot be - relayed through use of the word 'prayer'.

DeleteBrian.