Altare Domini: In 1662 'Table' means 'Altar'

The absence of 'Altar' from 1662 needs to be set alongside its consistent use in the post-Reformation Church of England. Eamon Duffy notes that the parson of Morebath - who conformed and ministered faithfully under the Elizabethan Settlement - continued, in parish documentation, to refer to his parish's new Communion Table as the 'Altar'. As Duffy comments:

The combination of the old sacral language of altars ... is instructive, and full of significance for the future. Already, however unwittingly, however tentatively, a new ceremonial sensibility was in formation.

Such "a new ceremonial sensibility" was not the avant garde and Laudianism: it was already evident in the mainstream Conformity of the Jacobean Church. Donne, that epitome of Jacobean Conformity, defended those who "love[d] the ancient forms, and doctrines, and disciplines of the church, and retains, and delights in the reverend names of priest, and altar, and sacrifice". To say of such a person "he is a papist", Donne warned, was a "hasty conclusion" and a "misinterpretation".

Anthony Sparrow's A Rationale Upon the Book of Common Prayer, first published in 1655, was to be republished on numerous occasions and would become the standard Anglican commentary on the BCP for the rest of the 17th century and widely used by 18th century commentators. Sparrow insists that 'Table' and 'Altar' are interchangeable terms:

Now that no man take offence at the word Altar, Let him know that anciently both these names Altar or holy Table were used for the same things, though most frequently, the Fathers and Councils use the word Altar. And both are fit names for that holy thing: For the holy Eucharist, being considered as a Sacrifice, in the representation of the breaking of the Bread, and pouring forth the Cup, doing that to the holy Symbols, which was done to Christs Body and Blood, and so shewing forth and commemorating the Lords death and offering upon it the same Sacrifice that was offered upon the Cross, or rather the commemoration of that Sacrifice, S. Chrys. in Heb. 10. 9. may fitly be call'd an Altar, which again is as fitly call'd an holy Table, the Eucharist being considered as a Sacrament, which is nothing else but a distribution and application of the Sacrifice to the several receivers.

To give some idea of the persistent use of 'Altar' in Anglican discourse throughout the 18th century, we can turn to Parson Woodforde. Here he is describing the Eucharist at Christmas 1773:

The Warden was on one side of the Altar and myself being Sub-Warden on the other side - I read the Epistle for the day at the Altar and assisted the Warden in going round with the Wine.

What all this suggests is that, over centuries, the use of 'Altar' was widely regarded by the theological and liturgical mainstream in the Church of England as entirely cohering with the BCP.

This is hardly surprising as official provision directed that the Holy Table should be furnished and respected as was the Altar. The Elizabethan Injunctions, even as they directed the orderly removal of altars, provided for significant continuity between pre-Reformation stone altars and post-Reformation Communion Tables:

And that the holy table in every church be decently made, and set in the place where the altar stood, and there commonly covered, as thereto belongs.

Parker's 1566 Advertisements likewise directed that the Holy Table should be furnished after the manner of an Altar:

Item, that they shall decently cover with carpet, silk, or other decent covering, and with a fair linen cloth (at the time of the ministration) the Communion Table.

This was also repeated in the Jacobean Canons:

We appoint that the same Tables shall from time to time be kept and repaired in sufficient and seemly manner, and covered in time of Divine Service with a Carpet of Silk or other decent Stuff ... and with a fair Linen Cloth at the Time of the Ministration.

When the Holy Table was vested like an altar and situated like an altar, it was only to be expected that the use of 'Altar' would continue, as it consistently did, in the post-Reformation Church of England.

Most significantly of all, perhaps, is that the BCP eucharistic rite itself encouraged the use of 'Altar', despite the absence of the word from the rite. Sacrificial language was significantly present in the rite and was regarded, even by Cranmer, as a legitimate expression:

Therefore when the old fathers called the mass, or Supper of the Lord, a sacrifice, they meant that it was a sacrifice of lauds and thanksgiving, and so as well the people as the priest do sacrifice; or else that it was a remembrance of the very true sacrifice propitiatory of Christ: but they meant in no wise that it is a very true sacrifice for sin, and applicable by the priest to the quick and dead.

For Sparrow, the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist was most evident in the post-Communion Prayer of Oblation:

This done, the Priest offers up the Sacrifice of the holy Eucharist, or the Sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving for the whole Church, as in all old Liturgies it is appointed, and together with that is offered up that most acceptable Sacrifice of ourselves, souls and bodies devoted to God's service.

Cranmer's recognition that part of the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist flows from it being the sacramental commemoration of the Lord's saving sacrifice is amplified by Sparrow:

besides these spiritual Sacrifices mentioned, the Ministers of the Gospel have another Sacrifice to offer, viz. the unbloody Sacrifice, as it was anciently call'd, the commemorative Sacrifice of the death of Christ, which does as really and truly shew forth the death of Christ.

The explicit description of the Eucharist as "commemorative sacrifice" became a commonplace of post-1662 Anglican eucharistic theology. For example, Brevint's The Christian Sacrament and Sacrifice (1673) - a mainstay of Anglican Eucharistic piety throughout the 'long 18th century' - identified "four distinct Sorts of Sacrifices" offered in the Eucharist:

1. The sacramental and commemorative Sacrifice of Christ. 2. The real and actual Sacrifice of themselves. 3. The Freewill Offering of their Goods. 4. The Peace-Offering of their Praises.

This very conventional account of the sacrificial nature of the 1662 Eucharistic rite thus led Brevint to repeat the also very conventional use of 'Altar':

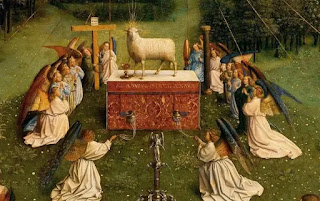

To men, it is a sacred table, where God's minister is ordered to represent from God his master the passion of his dear Son, as still fresh and still powerful for their eternal salvation; and to God it is an altar whereon men mystically present to him the same Sacrifice, as still bleeding and still suing for expiation and mercy.

This brings us back to Donne's reference to "the reverend names of priest, and altar, and sacrifice". Two of these terms, of course, were used throughout the Book of Common Prayer and were a source of controversy because of Puritan critiques. Donne's statement makes clear that 'Altar' is implied in the Prayer Book's use of the other two and that is therefore stands legitimately alongside them.

So why, then, is Altar not used in 1662? Its use was entirely normative. The Holy Table was, by official direction, vested after the manner of an Altar. And the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist was recognised by mainstream Church of England divines. We might suggest that, quite simply, 'Altar' was not required. By 1662 it was commonly accepted that 'Table' and 'Altar' were complementary, not contradictory, terms. The use of 'priest' and 'sacrifice' in the 1662 rite was also taken to imply that the Holy Table was obviously an Altar.

Above all, however, 'Table' - as previously discussed - was not a term which implied a 'low' view of the Sacrament; in fact, quite the opposite. Brevint indicates how the use of 'Table' was caught up with an affirmation of a true feeding upon Christ in the holy Eucharist:

For the Body of Christ, as the holy Fathers distinguish it, being of two Sorts, to wit, the Natural, which is in Heaven, and the Sacramental, which is blessed and given at the holy Table.

Here, 'Altar' is implied: for it is by feeding upon the Christ Crucified in the Sacrament, consecrated upon the Lord's Table, that the Lord's Sacrifice is made present and efficacious. As Bramhall asserted in his reply to a Roman apologist's claims that the Church of England had abandoned the Eucharistic sacrifice:

Seeing therefore the Protestants do retain both the consecration, and consumption or communication, without all contradiction, under the name of a Sacrament, they have the very thing, which the Romanists call a Sacrifice.

To feed upon the Lord's Sacrifice at the Table means that it is also an Altar, for there the commemorative sacrifice has been set forth. Brevint similarly points to the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist - and therefore 'Altar' - being necessarily implied by 'Table':

Therefore this Sacrifice being such, the holy Communion is ordained of Christ to set it out to us as such, that is, as effectual now at his holy Table, as it was then at the very Cross.

1662 did not need to say 'Altar' precisely because it said 'Table'. The meaning of the former is necessarily implied in the rite by the latter.

Comments

Post a Comment