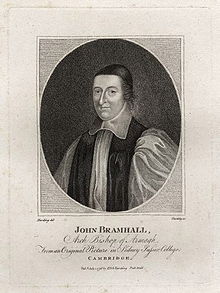

"It is high time both for you and us to renounce our own merits": Bramhall and a robustly Christocentric Reformed Catholicism

In An answer to Monsieur de la Militiere (1653) - a response to a Roman apologist - Bramhall defends the stance of the magisterial Reformation on justification, merits, and the invocation of Saints, identifying this with the teaching of "the ancient Church", and reminding us of the Protestant nature of Laudianism over and against Tridentine norms. Set alongside the other aspects of Bramhall's defence of the ecclesia Anglicana in this work, it points to a robustly Christocentric reformed Catholicism, richly sacramental, episcopally ordered because this is a divine institution and the apostolic order, rooted in patristic teaching and practice.

Concerning Justification, we believe that all good Christians have true inherent Justice, though not perfect according to a perfection of degrees, as gold is true Gold, though it be mixed with some dross. We believe that this inherent Justice and sanctity, doth make them truly just and holy. But if the word Justification be taken in sensu forensi, for the acquittal of a man from former guilt, to make an offender just in the eye of the Law, as it is opposed to Condemnation, 'It is God that justifieth, who is he that condemneth'; Then it is not our inherent righteousness that justifies us in this sense, but the free Grace of God for the merits of Jesus Christ.

Next for merits, we never doubted of the necessity of good Works, without which Faith is but a fiction. We are not so stupid to imagine that Christ did wash us from our sins, that we might wallow more securely in sin, but that wee might serve him in holiness and righteousness all the days of our life. We never doubted of the reward of good Works; 'Come ye blessed of my Father, &c. for I was hungry, and ye fed me'. Nor whether this reward be due to them in Justice; 'Henceforth is laid up for me a Crown of righteousness, which the Lord the just Judge shall give me in that day'. Faithful promise makes due debt. This was all that the ancient Church did ever understand by the name of Merits ...

It is an easy thing for a wrangling Sophister to dispute of Merits, in the Schools, or for a vain Orator to declaim of Merits out of the Pulpit, but when we come to lie upon our death-beds, and present ourselves at the last hour before the Tribunal of Christ, it is high time both for you and us to renounce our own merits, and to cast ourselves naked into the Arms of our Saviour. That any works of ours, who are the best of us but unprofitable servants, which properly are not ours but God's own gifts, and if they were ours are a just debt due unto him, setting aside God's free promise, and gracious acceptation, should condignly by their own intrinsic value deserve the joys of Heaven, to which they have no more proportion than they have to satisfy for the eternal torments of Hell: This is that which we have renounced, and which we never ought to admit.

If your Invocation of Saints were not such as it is, to request of them Patronage and Protection, spiritual graces, and Celestial joyes, by their prayers, and by their merits, (alas the wisest Virgins have oil in their Lamps little enough for themselves;) Yet it is not necessary for two Reasons; First, no Saint doth love us so well as Christ. No Saint hath given us such assurance of his love, or done so much for us as Christ. No Saint is so willing, or able to help us as Christ. And secondly, we have no command from God to invocate them.

So much your own Authors do confess, and give this reason for it, Lest the Gentiles being converted, should believe that they were drawn back again to the worship of the creature. But we have another command, Call upon me in the day of trouble, and I will hear thee. We have no promise to be heard, when we do invocate them; But we have another promise, 'Whatsoever ye shall ask the Father in my Name, ye shall receive it'. We have no example in holy Scripture of any that did invocate them, but rather the contrary; See thou do it not; I am thy fellow servant, worship God. We have no certainty that they do hear our particular prayers, especially mental prayers, yea a thousand prayers poured out at one Instant in several parts of the world ...

We do sometimes meet in ancient Authors, with the Intercession of the Saints in General, which we also acknowledge; or an oblique invocation of them (as you term it,) that is a prayer directed to God, that he will hear the intercession of the Saints for us, which we do not condemn; Or a wish, or a Rhetorical Apostrophe, or perhaps something more in some single ancient Author: But for an Ordinary Invocation in particular necessities, and much more for public Invocation in the Liturgies of the Church, we meet not with it for the first six hundred years, or thereabouts; All which time and afterwards also, the common principles and tradition of the Church were against it. So far were they from obtruding it as a necessary fundamental Article of Christian Religion.

From The Works of The Most Reverend Father in God, John Bramhall, Volume I.

One of the best articulations of Reformed soteriology ever written. All too often the intrinsic gift of sanctifying righteousness by the indwelling of the Holy Ghost, aka regeneration, is overlooked in Reformation circles by an exclusive focus on justifying righteousness for the merits of Christ alone. Bramhall redresses that error in good Pauline fashion by holding them together. You can definitely hear the echoes of Richsrd Hooker in this quotation; ditto the BCP.

ReplyDeleteExcellent summary. I think this does point to how the Caroline Divines - because they were removed from the initial struggles of the Reformation era and the dynamics these forced on debates and formulations - could articulate a mature Reformed Catholic vision.

Delete