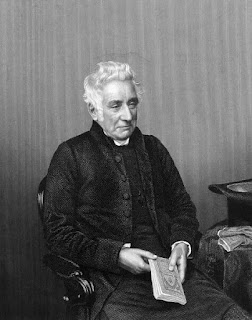

In the last year of his life, 1867, John Lonsdale, Bishop of Lichfield, had to address one of the most theologically and culturally divisive aspects of Anglo-catholic practice in Victorian England: auricular confession. The promotion of auricular confession, as

Nockles notes, was one of the most profound differences between the Old High tradition and the Tractarians: "Forgiveness was effectively made conditional upon the sacramental absolution administered by a priest in private confession in a way which the old High Churchmen deplored".

As recorded in The Life of John Lonsdale (1868), the Bishop was required to address the matter because of the controversy surrounding a boys' school in his diocese allowing pupils "by the permission of their parents only, to come to confession, and to receive absolution, if they are unable (as the Prayerbook says) by the usual means to satisfy their own conscience, and require further comfort or advice". Lonsdale carefully defended the practice, making it clear that it must be distinguished from the auricular confession increasingly promoted by Anglo-catholics:

Now, if the confession, which is allowed occasionally at [the school], approached at all to what is called 'auricular confession,' that is, the confession of the Church of Rome, that would at once, in my mind, be a fatal objection to my having anything to do with the place. The Church of Rome requires confession. We are met here to support a Church of England institution. The Church of England does not require confession. The Church of England, I should say, does not encourage confession; but the Church of England, under certain circumstances, permits it. Now I wish to be thoroughly understood. I am speaking to members of the Church, those who are acquainted with its formularies. The Church of England says, when persons are preparing to go to the Holy Communion, if they cannot satisfy their own minds after anxious self-examination and prayer, 'Let them go to one of its appointed ministers and open their minds to him.' This is only under the circumstance of preparation for the Holy Communion ...

The Church of England supplies it under those particular circumstances, but only as a preparation for the Holy Communion. Nothing will be done here but what the Church of England, as anybody will see by looking in his prayer book, sanctions in her formularies.

Here we see a key Old High conviction: "the benefit of absolution" referenced in the first Exhortation in the Holy Communion was no justification for auricular confession. No full confession of sins was required for this ministry. It was distinctly related to preparation for reception of the Sacrament. It was neither required nor encouraged. It was solely for those who could not quieten their conscience by other spiritual means.

Once again, Lonsdale's teaching allows us to draw a similarity with what has been described as the 'low church' character of the Church of Ireland's 1878 revision of the Prayer Book. The view expressed in the 1878

Preface, rather than being a straight-forwardly low church, evangelical position, perfectly accorded with the Old High understanding articulated by Lonsdale:

upon a full review of our Formularies, we deem it plain, and here declare that ... no power or authority is by them ascribed to the Church or to any of its Ministers in respect of forgiveness of sins after Baptism, other than that of declaring and pronouncing, on God's part remission of sins to all that are truly penitent, to the quieting of their conscience, and the removal of all doubt and scruple; nor is it anywhere in our Formularies taught or implied that confession to, and absolution by, a Priest are any conditions of God's pardon; but, on the contrary, it is fully taught that all Christians who sincerely repent, and unfeignedly believe the Gospel, may draw nigh, as worthy Communicants, to the Lord's Table without any such confession or absolution.

Comments

Post a Comment