'Unspeakable Benefit and Comfort': Beveridge on receiving the holy Sacrament at Whitsun

But the great thing they did whensoever they met together, was to receive the Sacrament; so that their coming together was still upon this Account, Acts 20. 7, where by breaking of Bread we are to understand the Sacrament, as also wheresoever it occurs in the New Testament, because the principal thing in the Sacrament, even the Death of Christ, is signify'd by breaking of the Bread; and therefore saith the Apostle, 'The Bread which we break is it not the Communion of the Body of Christ'? 1 Cor. 10 16. Neither did they content themselves with receiving the Sacrament now and then, but it was their daily, their continual Employment, Acts 2. 42, 46. And therefore we cannot doubt but that on the Day of Pentecost when they met together, they did that which was the Work of every Day, even administer and receive the Sacrament of the Lord's Supper.

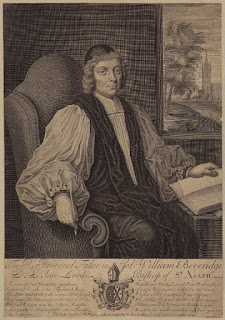

The context for this suggestion was the practice of celebrating the Sacrament at Whitsun, making it, with Christmas and Easter, one of those great feasts on which, in the words of the Prayer Book rubric, "every Parishioner shall communicate at the least three times in the year". Upholding this requirement was a pastoral concern which Beveridge shared with other divines in the late 17th/early 18th century Church of England, both those who stood, like him, in the Reformed tradition, and those who did not:

And verily I hope that there is none of you but have so confider'd what I suggested to you the last Lord's Day concerning the Necessity of receiving this Sacrament, that you are all prepar'd for it, being both asham'd and afraid to omit it any longer, as heretofore many of you have done; though I cannot but oftentimes wonder with my self with what Face any one can go out of the Congregation when the Sacrament of the Lord's Supper is to be administred, as if it was not as necessary for us to receive the Sacrament as it is to hear a Sermon ...

Note how Beveridge, the Reformed divine, emphasises that receiving the Sacrament is "as necessary" as hearing a sermon. As with his Ascension Day sermon, this Whitsun sermon here points to the 'unity and accord' which would shape the 18th century Church of England. That 'unity and accord' is also evident in the 'high Reformed' Eucharistic theology to which Beveridge gives expression. Contrary to Hoadleyite memorialism - a distinct minority view, regarded by the mainstream as associated with Socinianism - Beveridge asserted the teaching of the Prayer Book and Articles, that "Christ with all the benefits of his Death and Passion" was received in the Sacrament:

trusting in the living God, that he hath both excited and enabled you to prepare your selves for this blessed Ordinance: Let us all address our selves unto it; who knows but Christ may manifest himself to us as he did to the two Disciples in breaking of Bread? Who knows but the Holy Ghost himself may come down as he did in my Text, whilst we are receiving of the Sacrament, and fill our Hearts with all true Grace and Virtue? This I am sure of, that none of us shall receive it aright, but we shall also receive unspeakable Benefit and Comfort from it; which that we may do, let us bid the World adieu, and call in for all our scatter'd Affections, and present them before him that made them. Let us soar aloft for a while, and in our aspiring Thoughts contemplate nought but Christ. Let us fix the Eye of our Faith, so that we may look through the Signs to the Things signified; that so together with the Bread and Wine we may receive Christ with all the Benefits of his Death and Passion, and so may return home with our Sins pardon'd, our Lusts subdued, our Minds enlightened, our Natures cleansed, and our Hearts rejoicing in God our Saviour.

The language here employed by Beveridge has particular theological significance, on two grounds. Firstly, he is almost certainly echoing Article 17 on predestination:

As the godly consideration of Predestination, and our Election in Christ, is full of sweet, pleasant, and unspeakable comfort to godly persons, and such as feel in themselves the working of the Spirit of Christ, mortifying the works of the flesh, and their earthly members, and drawing up their mind to high and heavenly things ...

This is a good example of how Article 17 was interpreted during the 'long 18th century': not in the divisive, disruptive manner of the early 17th century, but quietly, modestly, and moderately as a means of underpinning, rather than undermining, the church's worshipping and sacramental life. Beveridge, therefore, employs it to describe the benefits of faithful reception of the Sacrament. This was the outworking and sign of the mystery of our election in Christ, rather than predestination being invoked over and against the church's ministry and sacraments.

Secondly, the use of 'comfort' in a Whitsun sermon inevitably brings to mind the collect of the day:

Grant us by the same Spirit to have a right judgement in all things, and evermore to rejoice in his holy comfort.

The Holy Spirit's ministry of gracious comfort is known in faithful reception of the Sacrament. There is similarly an echo of the collect for the Sunday after Ascension Day:

send to us thine Holy Ghost to comfort us, and exalt us unto the same place whither our Saviour Christ is gone before.

Here we see faithful participation in the church's sacramental life as a partaking of the Spirit. Ordinary Anglican piety, therefore, was a dwelling in the communion of the Holy Spirit, rather than life in the Spirit being defined as an experience apart from this.

On both counts, Beveridge points to receiving the Sacrament at Whitsun - the stuff of the ordinary piety of 18th century Anglicanism - as being to our "unspeakable Benefit and Comfort" because at Pentecost "he gave his Spirit to all his Disciples, whilst they were breaking of Bread".

Comments

Post a Comment