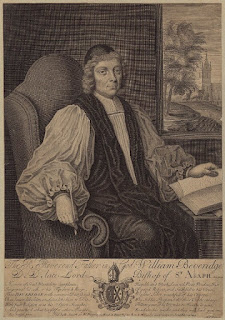

'What is substantial and necessary': from an Ascension Day sermon by William Beveridge

From whence we may observe by the way, how careful our blessed Saviour was to conceal nothing from us that might any way conduce either to our Salvation or Comfort. 'If it was not so,' saith he, 'I would have told you', and so he certainly would have told us many other things, which he hath not, if it had been necessary for us to have known them; and therefore we may conclude that whatsoever he hath not told us, it is no matter whether we know it or no. There are a great many nice Questions rais'd in Divinity, especially by the Schoolmen, which have perplex'd the Minds of the greatest Scholars, and have caus'd great Heats and Animosities in the Church, but they are generally of such things, which our blessed Master never thought good to determine, not to tell us any thing of them, which he would not have fail'd to have done, if either our future Happiness, or our present Comfort were any way concern'd in the Knowledge of thein which I therefore observe unto you that so you may not trouble your Heads with any impertinent Controversies about our holy Religion, which serve only to amuse and distract Men's Minds, and to divert them from what is substantial and necessary; what Christ hath taught you either with his own Mouth or by his Apostles, that you must believe and act accordingly, if you expect to be saved by him; but as for other things, let others dispute about them if they please, but do you rest satisfied in your own Minds that if it had been necessary for you to have known them, Christ would have told you of them, as he assures his Apostles, saying, 'If it was not so, I would have told you.'

What makes this extract particularly interesting is Stephen Hampton's inclusion of Beveridge in his list of Reformed divines in the post-1662 Church of England. Here Beveridge counsels against those "great many nice Questions rais'd in divinity". It is very difficult not to hear the echo of Charles I and Laud warning against "curious and unhappy differences" on the mystery of predestination and election. Placed alongside his celebration of the Church of England's "middle course" and as having "the pattern of the Primitive and Apostolical Church", this is a very good example of how the meaning and content of 'Reformed' - no less than 'Laudian' and 'Latitudinarian' - was (happily) revised in the post-1662 Church of England, shaped and influenced by the disastrous debates and divisions of the 1620s-30s and by a subsequent recognition of the need to secure peace of the Church. Above all, the extract points to the centre of the - to use the title of William Gibson's excellent study - 'unity and accord' in the Church of England during the 'long 18th century': a focus on "what is substantial and necessary" in doctrine, avoiding those debates over what was not necessary to the Church's confession. For "if it were not so, I would have told you".

Comments

Post a Comment