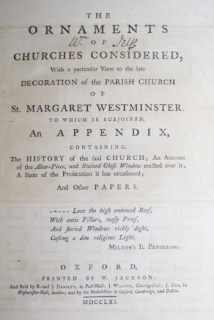

'If that be all the reason they have to banish Images out of the Church': a sermon from the 1640s invoked by an 18th century Anglican defence of imagery

Critics of the window deemed it 'superstitious'. The footnote points to how this echoed the iconoclasm of the 1640s:

During the civil Wars indeed, such pretended Abuses were assigned as Reasons for demolishing all such Windows.

As a rebuke of such iconoclastic arguments of the 1640s, the footnote turns to a 1645 sermon by "an eminent Divine of Oxford thus delivered his Sentiments to the learned Audience of that University". The preacher was Jasper Mayne, who was sequestered under the Commonwealth, becoming Archdeacon of Chichester at the Restoration. The sermon was pointedly entitled 'Against False Prophets'.

The significance of the sermon lies in how it provides further evidence of the retention and maintenance of modest imagery by the Elizabethan, Jacobean and Caroline Church:

Because it lightned when Socrates took the Ayre, one in the company thought that his walking was the occasion of the flash: this certainly, was a very vaine and foolish inference; yet not more vaine and foolish then theirs, who have taught people to conclude, that all pictures in Church-windowes are Idols, because some out of a misguided devotion, have worshipt them.

In mocking the iconoclasts of the 1640s, Mayne demonstrates how "ornaments", "windows", and "images" had been retained to, as The Ornaments of Churches describes it, "recall to Men’s Memories an historical Fact":

For here, if I should presse them in a rationall, logical way, (unlesse they will call Argument, and Logick, and Syllogisme, Superstition too, and banish Reason as well as Liturgy out of the Church) to think (as they doe) that Churches are unhallowed by reason of their ornaments, or to perswade people to refrain them, because some out of a blind zeale have paid worship to the Windows, is to me a feare as unreasonable, as theirs was, who refused to goe to Sea, because, there was a Painter in the City, who limned [i.e. depicted] Shipwracks. For certainly, if that be all the reason they have to banish Images out of the Church, because some (if yet there have been any so stupid) have made them Idols; by the same reason, we should not now have a Sun, or Moon, or Stars in the Firmament, but they should long since have dropt from Heaven, because some of the deluded Heathens worshipt them.

Any superstitious use of windows and images was, as Mayne emphasises, a misuse of such imagery: such, of course, was not the purpose for which imagery had been retained. Instead, the iconoclasm promoted by 'false prophets' in England of the 1640s was part of their wider "pretended strange visions":

Idolatrie in a Church window, Superstition in a white Surplice, Masse in our Common-prayer Booke, and Antichrist in our Bishops.

Rejection of modest imagery in the 1750s, therefore, was an echo of the false prophets of the 1640s and their violent hostility towards the Elizabethan Settlement.

Comments

Post a Comment